This article introduces a number of traditions found in Kyoto, and how they are reflected in its seasonal events, townhouses, and traditional sweets. It was prepared by Ryo Wakamura – a local guide!

The Basics

| 1 | Customs are practices and traditions related to daily life and events, handed down through generations in a community. |

| 2 | In Kyoto, both tangible and intangible customs have been preserved and passed on for generations. |

| 3 | Among them are Kyoto townhouses, the Obon festival during which ancestral spirits are welcomed home, and traditions surrounding Japanese confections. |

In this article

- Introducing Kyoto’s Many Customs

- Fire Prevention Talismans in the Kitchen

- Eating Minazuki on the Day of Nagoshi no Harae (Summer Purification Rites)

- Protection Against the “Demon’s Gate”

- Turning On Heat from the Day of The Boar

- Avoiding the Modori-bashi Bridge during Weddings

- Shōki, the Guardian Deity on the Roof

- Drinking Sake with the “Dai” Character Reflected in the Cup

- August 1st Traditions

Introducing Kyoto’s Many Customs

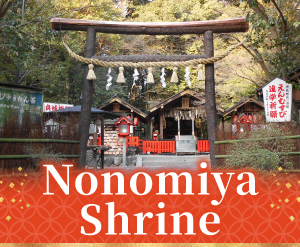

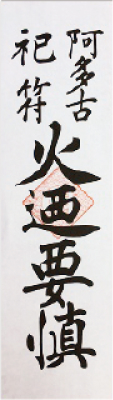

Fire Prevention Talismans in the Kitchen

In the kitchens of homes and restaurants, it is common to find a talisman inscribed with the words “Atago Shifu Hi-no-Yojin” (阿多古祀符火迺要慎), which can be directly translated to “The Atago Shrine talisman – handle fire with the utmost care.” Hanging it is believed to offer protection against fire.

From the night of July 31st to the early morning of August 1st, many people visit Atago Shrine to take part in the Sennichi Mairi (“Thousand-Day Pilgrimage”). It is said that one visit during this time grants the benefits of a thousand days of worship, so the shrine draws many visitors at this time.

There is also a custom called Sansai Mōde (“Three-Year-Old Visit”): if a child visits Atago Shrine before turning three, it is believed they will be safe from fire-related misfortune for life.

Eating Minazuki on the Day of Nagoshi no Harae (Summer Purification Rites)

At the end of June each year, shrines hold a ritual called Nagoshi no Harae. This Shinto ceremony is performed to cleanse people of impurities accumulated over the past six months and to pray for good health for the rest of the year. On this day, there is a custom of eating a Japanese sweet called minazuki.

The white part of minazuki is uirō, a steamed confection made from rice or rice flour, wheat flour, and sugar. Its triangular shape represents a block of ice, and the red beans sprinkled on top are believed to ward off evil.

Around a thousand years ago, when Kyoto was Japan’s capital, the imperial court observed the Ice Festival (Kōri no Sekku). At this event, people ate ice to pray for health during the hot summer months. The ice came from natural icehouses located in the mountains around the capital. Since ice was extremely precious and inaccessible for common people, they came to eat minazuki, a sweet made to resemble it, instead.

Protection Against the “Demon’s Gate”

At the northeastern corner of a house or building lot, you may sometimes see small white stones neatly arranged in a square. This custom is meant to provide protection from the “kimon” (Demon’s Gate)—the northeast direction, which is believed to be the entryway for evil spirits. Another commonly observed practice is to plant a nanten (heavenly bamboo) tree in the northeast. In Japanese, nanten sounds the same as “nan-ten” (literally, “to turn away misfortune”), so the plant is thought to have the power to ward off evil.

Based on this belief, as well as feng shui principles, shrines and temples in Kyoto were built in the northeast direction even a thousand years ago.

Turning On Heat from the Day of The Boar

In the old lunar calendar, months and days were represented by the twelve zodiac animals.

In ancient Chinese philosophy, all things were believed to comprise five elements: wood, fire, earth, metal, and water. Since the Boar corresponds to the water element, it was thought to suppress fire. For this reason, it was considered auspicious to begin using heating on the first day and month of the Boar, which usually falls around November. Doing so was supposed to ward off fire-related events.

There is also a custom of eating a sweet called I-no-Ko mochi (literally “boarlet rice cake”) on this day. Shaped like little boar piglets, these cakes are eaten as a form of prayer for protection from misfortune and for the prosperity of future generations.

Avoiding the Modori-bashi Bridge during Weddings

Modori-bashi is a bridge built over the Horikawa River of Kyoto. According to local custom, brides avoid crossing this bridge on their wedding day to prevent themselves from “returning” to their parents’ home after marriage.

The name Modori-bashi (literally “Returning Bridge”) comes from a legend: a monk who learned of his father’s death prayed to the gods and buddhas on this bridge, and his father miraculously came back to life for a short time. Since the word “modoru” in Japanese means “to return,” the bridge became associated with the act of returning.

Shōki, the Guardian Deity on the Roof

You may see figures of Shōki, a deity believed to ward off evil spirits, on the rooftops of Kyoto townhouses. Protective roof tiles called onigawara are placed on the roofs of temples for the same reason. Harmful spirits repelled by them were believed to instead endanger regular houses, which is why many of them display Shōki statues as a form of protection.

In Kyoto, it is common for a household to place a Shōki figure after a neighboring house has done so. When this happens, much attention is paid to their placement so that the figures do not face each other, avoiding a “staring contest” between the deities. The tradition of making Shōki figures from roof tile ceramic is said to have originated in Kyoto.

Drinking Sake with the “Dai” Character Reflected in the Cup

The Gozan Okuribi (“Five Mountains’ Send-Off Fires”) is a ceremony during Obon in which the spirits of ancestors, who were welcomed home for a few days, are sent back to the afterlife. On the night of August 16, fires are lit on five mountains in Kyoto, including Mt. Daimonji. The fires on this mountain are lit in the shape of the Japanese character “Dai” (大), meaning “great.”

There is a custom of holding a cup of sake so that the “Dai” character is reflected in the liquid, and then drinking it. It is believed that doing so will bring good health and protection from illness for the rest of the year.

Another practice involves taking the remaining charcoal after the fires have burned out, wrapping it in a piece of paper, and then hanging it at the entrance of the home. This is thought to serve as a charm to ward off misfortune and theft.

August 1st Traditions

August 1st is known in Japan as Hassaku Day. In the lunar calendar, Hassaku falls around the time when rice ripens, and it is also called Tanomi no Setsu (“Rice Harvest Festival”).

Since the Japanese word “tanomi” is synonymous with “request,” Kyoto merchants traditionally visit their clients on this day to greet them and maintain good relationships.

In Kyoto’s traditional entertainment districts, geiko (regional word for geisha) and maiko (apprentice geiko) wear formal black kimono and visit ochaya (traditional teahouses where geiko and maiko entertain guests) to offer their greetings as well.

Article Author

Ryo Wakamura of Rakutabi