Outline

Rakugo is a traditional Japanese comic storytelling artform. A single performer sits on the stage and tells interesting stories that are sentimental or humorous. Around 1680, three particularly talented performers, known as the Fathers of Rakugo, were recognized in the large cities of those days, Kyoto, Osaka and Edo (present-day Tokyo). The three masters earned their livelihood by telling stories to paying audiences.

Meanwhile, yose theaters dedicated exclusively to variety entertainment, including Rakugo, began to emerge. This art has been loved by the Japanese people for over 300 years.

In this article

Structure of Rakugo

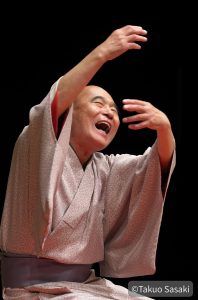

Rakugo is performed by a solo performer who sits at the center of the stage and tells hanashi (Rakugo stories). It is a very simple style of verbal performance, the story often consisting merely of conversations among the characters. The performer thus portrays numerous different characters by her/himself, expressing a variety of emotions and situations with skillful gestures. A hanashi always ends with an ochi, or punch line.

Makura

Performers do not jump right into the story proper. Rather, it is customary for them to first engage in small talk or share anecdotes that tie into the main story. This is called makura (literally “pillow”). One can think of this as a warm-up, in which the “pillow” of everyday topics allows the performer to get a feel for spectators’ mood and interests that day.

Hanashi

The hanashi span a wide variety of plots. Some have extraordinarily unique characters. Others depict the love between a husband and a wife or among family members, which can even move the audience to tears. Stories feature seasonal events such as the New Year or Hanami cherry blossom viewing. The length of the hanashi varies, some lasting only about ten minutes or so, while others continue for over one hour. There are more than 300 stories currently being performed.

Ochi (also called Sa-ge)

Another important element of Rakugo is the ochi—a punch line delivered to bring the story to an end. There are various types of ochi—some include witty puns and others bring together hints provided earlier in the story.

Kamigata Rakugo and Edo Rakugo

Rakugo evolved at almost the same time in the cities of Kyoto, Osaka and Edo, when a master of Rakugo appeared in each city. It developed slightly differently in each city, and today there are two distinctive traditions: Kamigata Rakugo and Edo Rakugo. Different stories are performed in Kamigata (old name for the Kansai region of Japan) and Edo/Tokyo, but many of those told in Edo/Tokyo were originally imported from Osaka.

Kamigata Rakugo: Rakugo in Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe

Kamigata Rakugo began with people earning money from telling stories in shrine precincts. To gain the attention of passers-by, the performer used small props such as kobyoshi (wooden clappers) to make sounds. Characters were portrayed in an intimate manner using dialects from Osaka, Kyoto and elsewhere, not standard Japanese. Following World War II, Kamigata Rakugo fell into decline, but today there are more than 250 artists in Kamigata alone.

Edo Rakugo: Rakugo in Edo (Tokyo)

Rakugo in Edo developed as wealthy patrons invited performers to their residences and other venues to tell stories. It thus became a “parlor art” where performers did not need to employ noise-making tools, so it became a more subtle recitation for subdued spectators. Today, there are nearly 800 Rakugo performers active in Tokyo.

Props used in Rakugo

Common Props used in Kamigata and Edo

– 1. Costume: Rakugo performers wear kimono.

– 2. Zabuton: The performer kneels on a square cushion placed at the center of the stage.

– 3. Sensu: A folding fan is an essential stage prop for Rakugo. The performer uses it to represent various objects such as an oar or pipe when folded, or a large sake cup when opened fully.

– 4. Tenugui: A hand towel is used to represent a wallet, letter, book, tobacco pouch, and much more. Each Rakugo performer has their own specially-designed tenugui.

– 5. Mekuri: A large vertical paper sign on which each performer’s name is written is displayed during their performance (only in Kamigata style)

Props used only in Kamigata

hiza kakushi (knee screen) (6), kendai (7), kobyoshi (8) (table, clappers)

Kendai is a small table set on the stage. It is struck with kobyoshi (wooden clappers), the sharp rapping sound signaling a scene change or to show the passing of time. Hiza kakushi (knee screen) is a low partition placed in front of the kendai. Kamigata performers move around a great deal, so this is used to hide the performer’s legs from the audience in case their kimono becomes disheveled.

Hiza kakushi, kendai and kobyoshi are placed as a set onstage, although not all Kamigata Rakugo stories require them.

Yosebayashi

Yosebayashi is a collective term for the music, including debayashi, played when a performer enters the stage, and hamemono, played for atmospheric effect during the performance. Instruments such as the shamisen, flutes, drums, and gongs are used.