Brief Overview

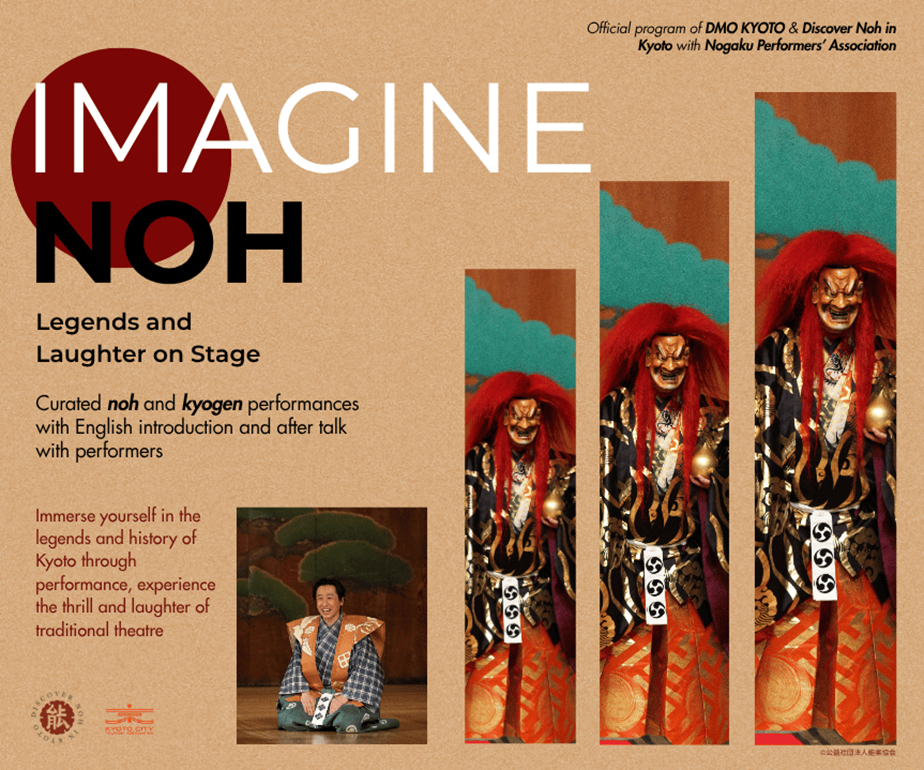

Noh and Kyogen are two deeply traditional Japanese stage performances. Nohgaku is a term which includes both Noh and Kyogen. The origin of Nohgaku lies in “Sarugaku” – performance art forms that were centered on nature and Buddhism. They were brought to Japan from the Korean Peninsula and mainland China, and merged with the indigenous faith of the Japanese people. The form of Nohgaku that we know today was established during and after the Edo period (1603-1868). During the Meiji period (1868-1912), when Japan experienced drastic Westernization, Sarugaku was renamed Nohgaku. In 2001, Nohgaku was included in UNESCO’s Proclamation of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, and in 2008, it was designated an Intangible Cultural Heritage. This unique traditional Japanese performance art form has had a global influence on avant-garde artists of drama, dance and music.

In this article

What is the Noh / Kyogen theater?

Noh

Noh, a stage performance somewhere between a play and opera, consists of utai (vocals) and mai (dance). Often featuring a ghost, god or demon portrayed by an actor wearing a mask, its stories are usually tragic. Noh flourished with Zeami Motokiyo, son of Kan’ami, in the 15th century. It was highly valued and protected by aristocrats and samurai feudal governments.

[Styles of Noh]

There are two different styles of Noh dramatic stories.

Mugen Noh

A typical plot of Mugen Noh has a historical or legendary figure in the main role. This narrative style, developed by Zeami, has a priest or traveler summon the spirit of this deceased person from the afterlife to relate a tale about a turning point in their past.

Genzai Noh

The main character of Genzai Noh plots is a living person dealing with events in the real world, and the story develops over the course of time in a linear fashion. It often features the emotional state of the lead character caught up in a dramatic situation, consisting of much dialogue among the characters.

Kyogen

Kyogen is a type of stylized comedy, a dialogue-based theater that contains exaggerated movement and vocalization. The stories feature slapstick and satire with a focus on the daily life of common people or folktales. Characters are often a boss and his subordinate, colleagues, a husband and wife, farmers, neighbors, merchants or wealthy people from other regions, and thus provide a sense of familiarity to the audience. Imaginary creatures such as goblins, deities and spirits sometimes appear, but they wear rather comical costumes and masks and are never as intimidating as in Noh. One of the key differences from Noh is that Kyogen plays involve only two or three characters. The normally unmasked performers set the mood with lively dance and song.

Roles in Noh

A Noh performance is made up of performers with distinctly different roles. This section introduces these roles and their individual responsibilities.

1. Shite-kata

The actor playing the main character is called “Shite”. Shite almost always wear masks. According to the plot, there may be special stage settings called “tsukuri-mono,” which Shite must build. It is also the responsibility of the Shite to decide on the casting. A Shite actor, in other words, is at the same time the main character, producer and scenographer.

2. Koken

The Koken is a stage assistant. In the ritual context of Noh performance, this is an essential role, as Koken must stand by in case of an emergency when one of the performers cannot continue. Usually, an experienced Shite actor takes the position of Koken. The Koken assists with costuming backstage and even on stage as well.

3. Jiutai

Jiutai are the chorus, responsible for utai (singing). Shite-kata actors take this role.

4. Waki-kata

The Waki-kata actor plays the role called “Waki” (accompanying player). Generally, Waki facilitate the story, standing between the Shite (main character) and the audience. Waki always portray living, male characters such as a Shinto priest, Buddhist monk, or samurai. This role does not employ a mask.

In many Noh pieces, the performance begins with a song by the Waki on the main stage. Whether the Shite appears quietly as an ephemeral spirit, or dances energetically, the Waki always watches the Shite, kneeling quietly from a corner of the stage.

5. Kyogen-kata

Kyogen-kata perform as actors in the comic plays, as well as Koken and Jiutai. During acts of a Noh performance, Kyogen-kata also appear on stage as a local priest or resident to narrate a related story or to answer the Waki’s questions concerning the place or ghost he has just encountered. Another important role of the Kyogen-kata is to act in a piece called “Sambaso,” which is a dance performed in the latter half of the “Okina” piece. Okina is a special piece performed on auspicious occasions such as the New Year.

6. Hayashi-kata

Hayashi-kata are musicians. Four musicians play four different instruments: a flute (fue), a small hand drum (ko-tsuzumi), a large hand drum (o-tsuzumi) and a large drum (taiko). A Hayashi-kata specializes in one particular instrument.

Learn more about Noh

Costume

The kind of costume worn by the Shite (main character) depends on their role, but it is usually gorgeous and multi-colored: red, vermillion, blue or gold. This kind of splendid costume is not possible to wash completely because its materials are too delicate and decorated with gold leaf and elaborate embroidery. Surprisingly, some costumes have been in use for over a few centuries. Rather than gorgeous robes, the Waki (supporting role) usually wears a simple costume called mizugoromo, the everyday attire of elders and Buddhist monks.

Masks

There are approximately 60 kinds of basic Noh masks portraying young women, old men, young and old samurai, Hannya (female demons), and so on. When masks began to be used in Noh performance is unknown. Since ancient times, mai, or dance, is one of the most important offerings to the deity, and the performer of the mai was believed to be the vessel for the god. In the Noh pieces, a mask is an essential tool for the performer to become one with the deity on the stage. In Kyogen, masks are rarely used, and when they are they are for more down-to-earth deities like Fukunokami (the God of Happiness), and animals (mosquito, dog, fox) or unsightly women.

Fan

An ogi, or folding fan, is another indispensable tool in a Noh performance. Not only is it used during the mai (dance), but the performer skillfully adapts a fan to resemble a sake cup, a sword, a letter or other items in the story. The fan is also used for more realistic mime in Kyogen, accompanied by onomatopoeic sounds for sawing wood (zuka-zuka) or opening a sliding door (sara-sara). Fans are painted with appropriate seasonal or natural designs, determined by the play.

Noh Stage

Remarkably, the Noh stage has a roof, so that it looks like an independent structure inside another building. This is because Noh was originally always performed outdoors, thus a Noh stage existed as a separate building. Only from the Meiji period (1868-1912) has the Noh been staged indoors. There is no drop curtain between the stage and the audience.

Whether outdoors at a shrine or temple, or indoors at Kyoto’s several theaters, the dimensions of the main stage and four pillars remain unchanged. This means that actors feel at home wherever they perform.

Pine Tree on the back wall

A large pine tree is depicted on the back wall of the Noh stage. Since pine trees are believed to be the place where the deity descends, every Noh stage has a painting of a pine tree, said to express permanence.