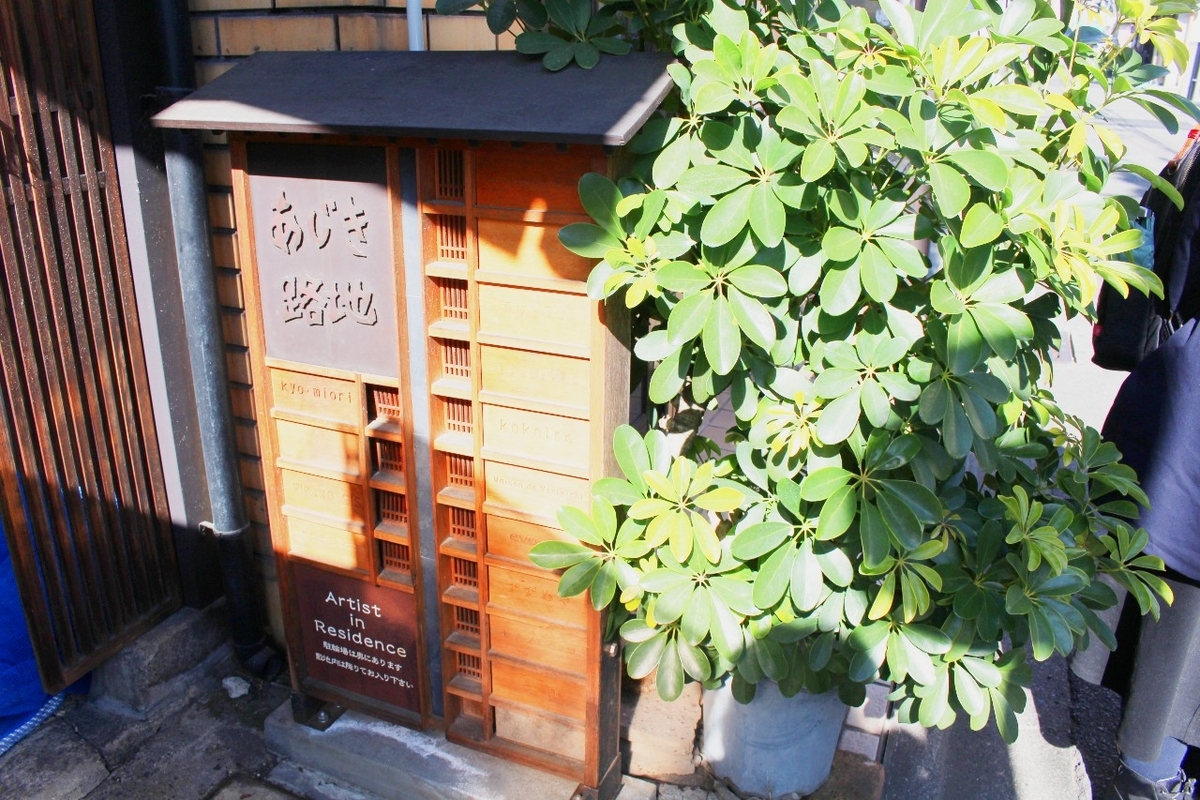

The narrow alleys, lined with lattices painted with bengara (red iron oxide) and houses facing each other with their eaves nearly touching, provide a landscape that is unique to Kyoto. Ajiki Roji (or Ajiki Alley) in Higashiyama Ward has been a cultural and artistic hub that has supported young artists and craftspeople for the past 20 years. Selected as a “Company Committed to Excellence in Ethical and Sustainable Tourism Business Practices” under the “Kyoto Guidelines for Sustainable Tourism” actively promoted by Kyoto City.

Company Committed to Excellence in Ethical and Sustainable Tourism Business Practices

Kyoto Guidelines for Sustainable Tourism

The traditional Japanese lifestyle of combining the home and workplace, watched over by the “mother” of the tenement houses

A “rōji” (meaning “alley”) generally refers to a narrow passageway or backstreet, but in Kyoto, it is often used to refer to a cul-de-sac, and is pronounced “rōji” in the Kyoto dialect.

The history of these alleys dates back to the founding of Heian-kyo, one of several former names for the city now known as Kyoto, when the city was planned based on the framework of a grid pattern divided into “ōji” (major streets) and “koji” (minor streets). Because each of the blocks surrounded by the main street is quite large, as the population grew, more and more houses and shops were built within them. As a result, alleyways were created so that people could access the center of these blocks, and communities unique to the city were formed as shared spaces where people helped each other in their daily lives.

The traditional tenement houses built over 110 years ago in this particular alley are managed by a woman named Hiroko Ajiki. When she inherited the tenement houses from her mother in 2004, she and her late husband wondered if they could do something more than just lease them out and collect rent, and instead support the endeavors of young artists and craftspeople. After getting married, Hiroko decided to give up her dream of becoming a metal engraver and instead provide affordable places for young people to live so that they could focus on their creative activities. She adopted the traditional rule that residents must live and work in the same place, and that she would not accept tenants who only wanted to use the space as a home, a store or a workshop, or who only wanted to stay there for a short period of time.

Among the residents who look up to and refer to Hiroko as “mother”, there have been many young people who have grown up and left the area, but who have continued to visit her from time to time, even after they have moved away, and Hiroko has continued to maintain a relationship with them, caring for them as if they were her own children.

Over the years, Morio, Hiroko’s only son, has provided much-needed support in the management and repair of the tenement houses. After quitting his job at the end of 2021, he opened a coffee shop in the main house at the entrance to the alley in the spring of the following year, and has been focusing on new initiatives such as disseminating information about the alley and holding events while running his shop.

The scenes of everyday life and new initiatives emanating from the alley

The scenes of everyday life that continue to thrive in Ajiki Alley have attracted attention from people both in Japan and overseas, even being featured in a commercial for JR Tokai. The Ajikis have also given interviews to national and municipal governments, providing information on landscape preservation and the support and dissemination of cultural arts.

Since 2021, they have partnered with The Celestine Kyoto Gion, a nearby hotel, to offer alley tours to hotel guests, and the accompanying explanations and information on Kyoto’s alley culture have been particularly well received by tourists from overseas.

In order to utilize the landscape of the alley as a tourist resource and pass it on to future generations, the building exteriors have been preserved from the time they were built as much as possible, including the protruding lattices painted with natural bengara pigment containing persimmon tannin and the plaster walls. “It takes a lot of effort and money, but we try to repair the houses using traditional methods,” says Morio. Taking into consideration the preservation of the alley’s nighttime scenery, all the exterior lights are fitted with warm-white light bulbs to create an atmosphere that captures the distinctive feel of Kyoto’s alleys.

In addition to simply preserving what has been passed down, new developments have also been initiated, and the empty plot of land at the end of the alley, which had previously been paved with concrete, has been turned into a green space in the form of a Japanese-style garden. The garden, which is filled with native tree and plant species such as red and white plum trees, cedar moss, and glabrous sarcandra herb, provides a place for residents to relax and to welcome tourists on guided tours.

What the alleys of Kyoto can do now for local residents and visitors alike

Although Morio is working to disseminate information to support the creative endeavors of the residents, the sale of their works, and the promotion of their activities, he says that the fact that Ajiki Alley has become a well-known place has also led to an increase in the number of problems he encounters. In addition to breaches of etiquette such as sightseeing during certain times of day that would disturb the neighbors, or talking loudly, some people have started to take photos without permission or hold paid events, and the Ajikis began to think that “if people don’t understand that this is not just a tourist spot but also a residential area where people actually live, it will become a nuisance to the residents and defeat the purpose of their efforts.” To prevent these things from happening, they decided to post notices at the entrance to the alley, and to make them easily noticeable without spoiling the scenery, they made them in the form of a komafuda (traditional wooden signboard) to ask visitors for their understanding.

To ensure the safety of both the residents and visitors, they also cooperated with the shops that moved into the tenement houses during the pandemic to install disinfectant dispensers as certified shops working to prevent the spread of infections, and drawing on the lessons of the large fire that broke out in the nearby geiko and maiko district of Miyagawa-cho, they installed automatic fire alarms that use electricity in all the tenements in 2021. They set up a system that would immediately notify the Ajiki family in the event of a fire, and they also installed fire extinguishers in each house and distributed instructions on how to use them so that each resident would be able to take initial action should a fire break out. Considering the fact that the alley leads to a dead-end, they also established another route to the main street that could be used in the event of a disaster, and made sure that all residents were aware of it. While it is of course important to protect the lives of the residents, it is also necessary to provide information to help them lead fulfilling lives, and Hiroko notes that “One of the challenges we will face in the future is to maintain a balance between both of these aspects.”

In Kyoto, there are many cases where traditional townhouses that were previously used as residences have been converted into shops and put to new use, a method that is particularly popular as a way of responding to inbound demand, but Morio raises the issue of passing on a lifestyle culture that goes beyond just the buildings themselves, saying, “I think that rather than just being a place where visitors can buy things or enjoy a meal, there is also value in being able to experience the lifestyle and livelihoods that remain in these traditional townhouses.”

Although roughly 80% of the customers who visit Morio’s coffee shop, fuku coffee roastery, which is located at the entrance to the alley, are tourists from overseas, through interacting with the people who visit and talking with them about the alley, the townhouses, and life in Kyoto, Morio notes, “Many people value the desire to gain knowledge and experience something for themselves, rather than just looking at things and enjoying them while traveling. I’m currently trying to see if this can serve as a hint for what’s to come.”

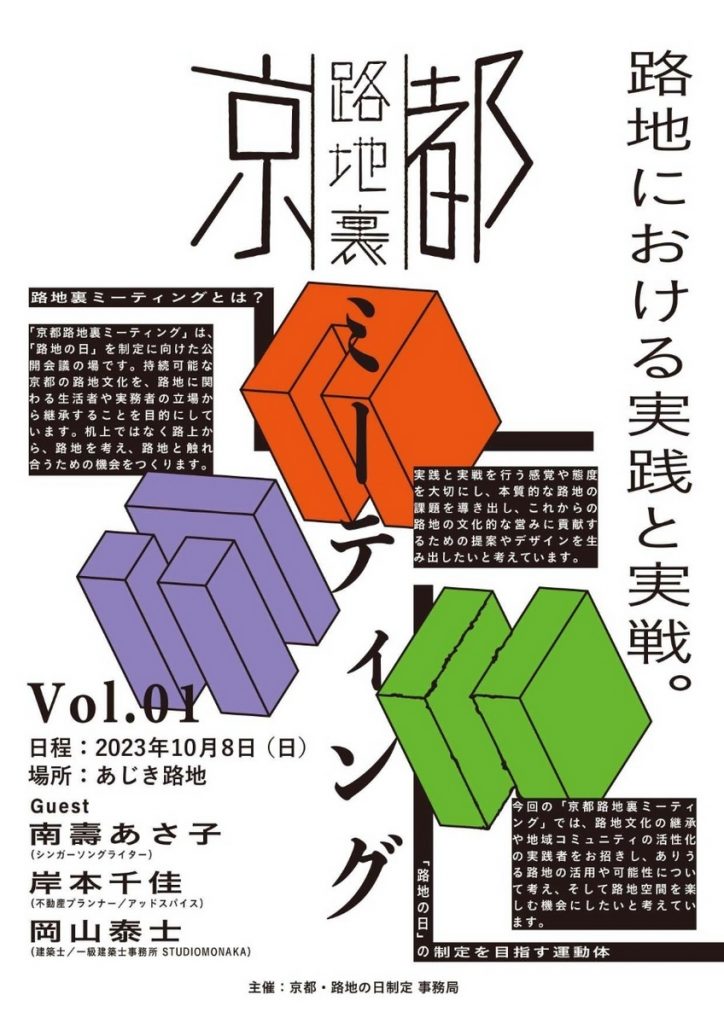

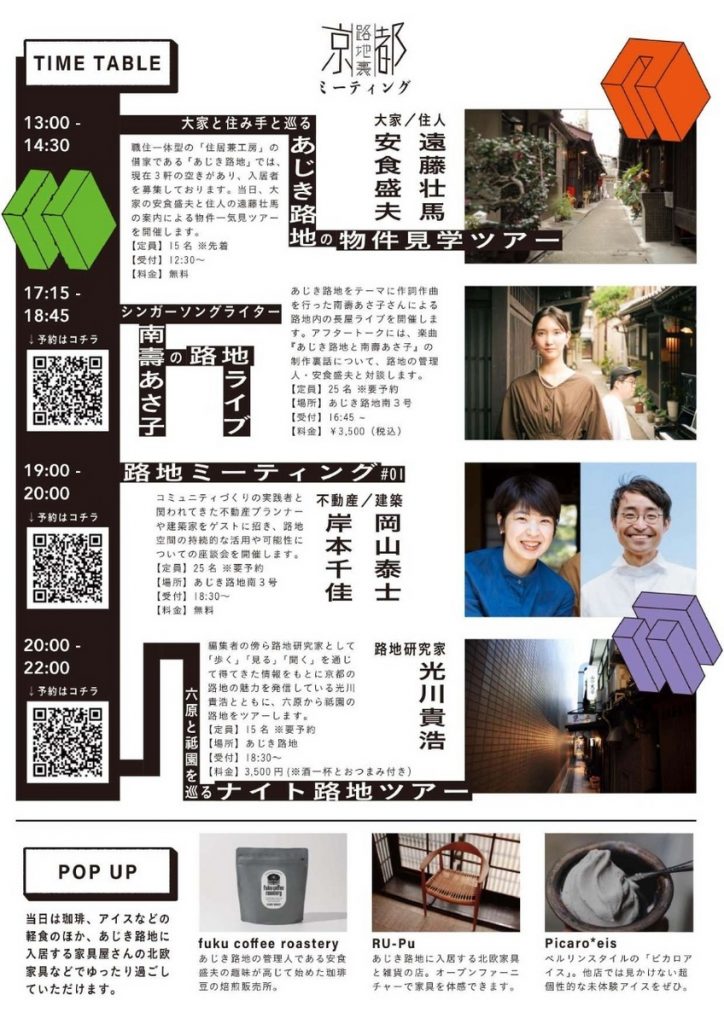

Connecting the back alleys of Kyoto through “Kyoto Roji no Hi” (Kyoto Alley Day)

Morio is also active as one of the organizers of the “Kyoto Roji-ura Meeting” (Kyoto Back Alley Meeting) event. The first event was held at Ajiki Alley in the fall of 2023, featuring a discussion on how to utilize the more than 10,000 alleys in Kyoto as tourism resources and places to disseminate information. The objective of this event is to pass on the sustainable alley culture of Kyoto from the perspective of the people and professionals involved in them on a day-to-day basis.

They have also been holding meetings with other interested parties on a monthly basis with the aim of designating June 2 as “Kyoto Roji no Hi” (Kyoto Alley Day). These events require a great deal of help from volunteer staff and others, so if you are interested in Kyoto’s alley culture, why not get involved?

■Related links

[Kyoto Guidelines] Collection of Good Practices

Ajiki Alley | Row of tenement houses for young artists in Higashiyama, Kyoto (Japanese only)