TEXTO DE: Aki Igarashi

Director de la Cooperativa Industrial de Patrones de Diseño de Nishijin

¿Por qué se denomina a la tela Nishijin-ori una tela de lujo?

La tela tejida se crea entrelazando hilos de urdimbre y trama para formar una superficie plana, y los nombres específicos de las telas varían según el lugar donde está hecha la tela o de qué materiales.

La zona alrededor de Imadegawa Omiya fue el cuartel general del ejército occidental, controlado por Yamana Sozen, durante la Guerra de Onin hace aproximadamente 550 años, lo que llevó a que esa zona se llamara "Nishijin" ("Campamento Occidental"). Por ello, la tela tejida allí se conoce como "Nishijin-ori (ori, que significa 'tejido').”

Famosa por su variedad de colores y apariencia tridimensional, la tela Nishijin-ori es una tela de seda tejida con hilos teñidos. Los hilos de seda, hilados a partir de capullos de gusanos de seda, se tiñen primero y luego se utilizan para la urdimbre y la trama. La tela final se teje en varios telares, exclusivos de cada empresa productora.

Hilos que se hilan a partir de capullos de gusanos de seda. Los hilos se enrollan cuidadosamente mientras los capullos se cuecen a fuego lento en agua caliente. Sin el cuidado adecuado, estos hilos se enredan, se apelmazan o se rompen, por lo que se requiere una gran habilidad.

El proceso de tejido. En el cuento popular japonés «Tsuru no Ongaeshi» («La grulla devuelve un favor»), la grulla teje de esta manera.

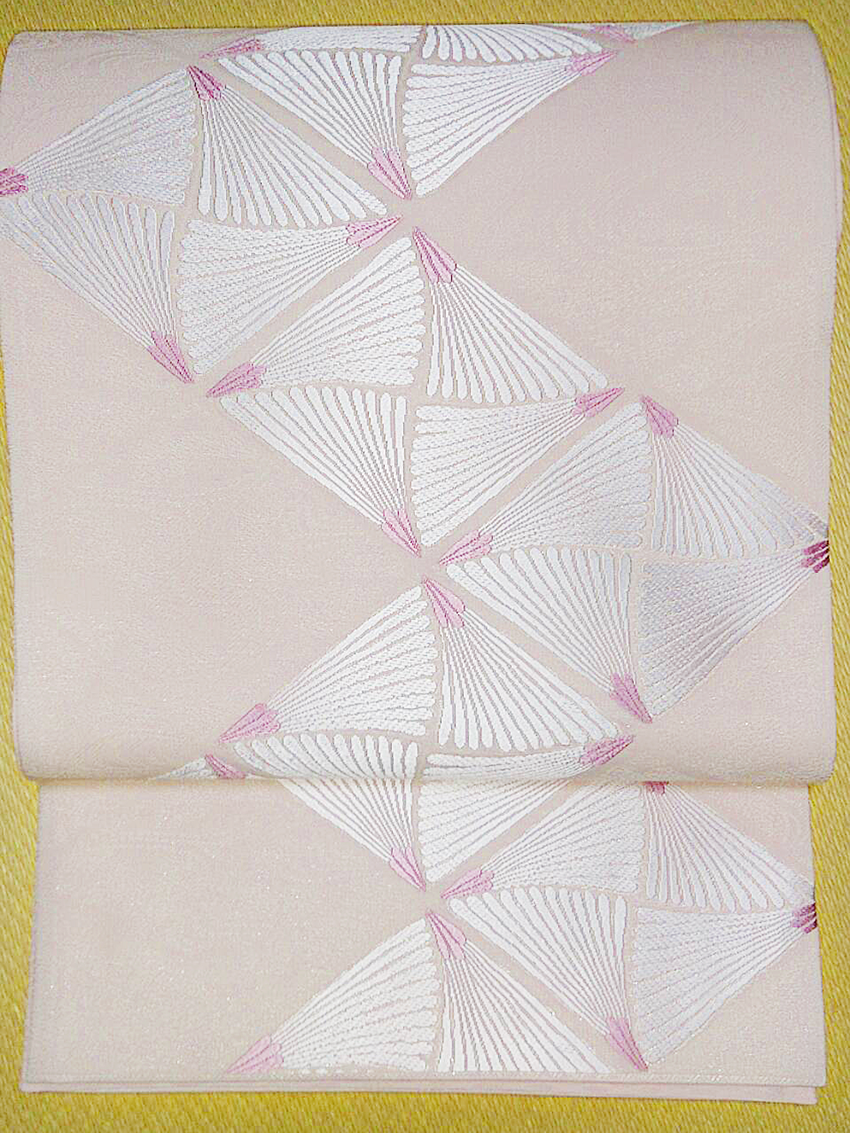

Hay muchos productos hechos con tela Nishijin-ori, pero los artículos más comunes en los que la gente pensaría son obitela de kimono, kesa y corbatas. Otros productos incluyen hiosogiro (tela para montar pergaminos y pinturas) y ningyogire (tela para ropa de muñecas tradicionales Hina).

Una foto de un obi

Si bien el hecho de estar tejida con seda es una de las razones por las que la tela Nishijin-ori se considera una tela de lujo, personalmente creo que el equipo de telar utilizado para crearla es otra razón importante. Algunos ejemplos de componentes clave del equipo de telar incluyen... boto y fumise que controlan los hilos de urdimbre; hibako caja de transporte, la hikibaku dispositivo para incorporar pan de oro y la tsukidashi herramienta que controla todos los hilos de la trama; y la furioso, tarume y tasuke Necesario para tejer ropa de verano. Existen diversos tipos de telares en todo el mundo, pero sin duda ningún otro posee componentes tan ingeniosos y complejos.

Los tejidos tienen una larga historia, ya que fueron traídos de China y transformados de forma única en Japón hasta alcanzar su estado actual. Creo que los japoneses tienen un talento especial para adaptar creativamente artículos de otros países a sus gustos. Además, Kioto fue la antigua capital y los artesanos competían ferozmente entre sí, esforzándose constantemente por crear mejores productos, mientras tejían sedas de lujo en una organización dirigida por la corte real de Heian, lo que dio lugar a innovaciones extraordinarias. Este espíritu aún perdura en el Kioto actual. Creo que esto se aplica no solo a la tela Nishijin-ori, sino a toda la producción tradicional de Kioto.

De dónde proviene el nombre “Santuario Tama-no-Koshi” y el proceso de diseño del patrón

Mi trabajo, dedicado exclusivamente a la elaboración de diseños de patrones, fue concebido por primera vez hace aproximadamente 360 años por Sonko Okamoto. Un monumento en su honor se alza en el extremo norte del Santuario Imamiya-jinja, frente al subsantuario Orihime-sha en Kita-ku, Kioto. Me estoy desviando un poco del tema, pero el Santuario Imamiya-jinja también se llama "Santuario Tama-no-Koshi", en honor a Otama, hija del dueño de una frutería, quien fue la concubina favorita del general shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu, y quien posteriormente sería llamada Keishoin por ser la madre biológica de Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, convirtiéndose en un símbolo de ascenso social a través del matrimonio.

La producción de telas Nishijin-ori implica numerosos procesos y se crea dividiendo el trabajo entre su comunidad empresarial, donde cada entidad comercial o artesano independiente se especializa en diferentes procesos de producción. Primero, la tienda textil elabora una propuesta inicial de producto. A continuación, el diseñador crea un diseño adecuado y el patronista crea una plantilla. Mientras tanto, el tintorero tiñe los hilos de urdimbre y trama que se utilizarán, un urdidor urde el telar y un tejedor prepara el telar para los hilos de trama y realiza el tejido. El material tejido se procesa según su propósito y se crea el producto final.

La ventaja de esta división del trabajo reside en la experiencia en cada uno de los diversos campos, además de garantizar la conservación de técnicas avanzadas. La desventaja es que el producto no puede completarse si falta algún paso.

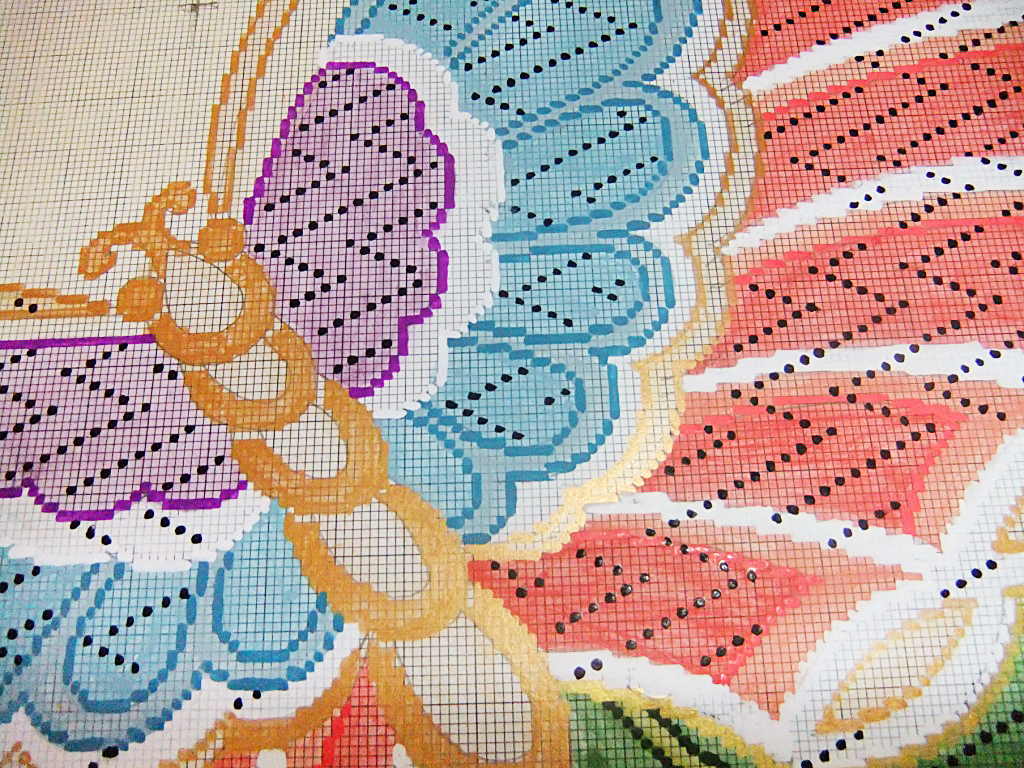

Una de las muchas funciones es la de diseñador de patrones, que consiste en crear una plantilla para el diseño final de la tela tejida. A partir de un diseño propuesto a escala real, el diseñador de patrones selecciona papel rayado especial (similar al papel milimetrado) que se ajusta a las especificaciones del telar y luego copia a lápiz una versión ampliada del patrón en el papel antes de añadir color para que coincida con el producto final previsto. Finalmente, el diseñador de patrones marca cuidadosamente las líneas finas a lo largo del papel, completando la plantilla del diseño final.

La plantilla de diseño

Una vista de cerca de la plantilla de diseño

Un obi completo para un kimono furisode formal

Después, se escanea la plantilla y los datos del patrón se proyectan como imagen en una computadora. Se combinan los archivos adjuntos que muestran la textura de la tela tejida y las instrucciones para mover los hilos de trama, y se ingresan los datos según los estándares de datos de patrones CGS. El producto tejido final puede entonces crearse utilizando telares automáticos. Hoy en día, aunque el trabajo se realiza principalmente en computadoras, es habitual que los datos se almacenen en disquetes de 3,5 pulgadas. Los artesanos envejecen cada vez más y no pueden usar los nuevos medios con comodidad.

La plantilla de diseño

El diseño propuesto

Lo que mi trabajo significa para mí

Mi abuelo fundó el negocio familiar después de la guerra. Pasó de mi abuelo a mi padre, de mi padre a mi madre, y ahora lo llevamos adelante mi hermana y yo. Al mostrar este trabajo, a menudo oigo a la gente decir: "Es un trabajo muy minucioso, ¿verdad?". Pero como lo he observado desde mi infancia, y supongo que soy de los que se dedican a las cosas, no pensé mucho en ello; solo quería ayudar a mi madre, que estaba tan ocupada. En aquel entonces, durante la burbuja económica japonesa, me daba vergüenza explicar que mi trabajo consistía en crear productos tradicionales japoneses. Pero ahora, a menudo recibo comentarios como "¡Guau, es increíble!", y creo que los tiempos han cambiado. Hoy en día, siento que la continuidad tiene un poder especial.

Se suele decir que no se puede hacer este trabajo sin un buen dibujo. Y sí, para crear hermosos productos tejidos, se necesita cierta habilidad artística para completarlos según el concepto de diseño propuesto. Pero otros factores también son importantes, como las consideraciones propias de un programador al cuantificar y combinar para no desperdiciar hilos ni sobrecargar los movimientos del telar.

Siento alegría y una sensación de logro cuando el tejedor logra tejer algo tan complejo y difícil sin cometer errores. Siempre tengo cuidado, ya que cualquier error puede dificultar el resto de las etapas del proceso de producción, pero, por supuesto, hay veces en que mi parte no sale bien. Me siento muy mal cuando esto sucede, pero me digo a mí mismo: «La gente de antes podía hacer esto, así que yo también puedo» e intento cambiar de mentalidad. Y, por último, es importante disculparse sinceramente y corregir cualquier error. A veces puede ser sorprendentemente difícil hacer algo aparentemente sensato después de la edad adulta, pero intento abordar cualquier error con rapidez y sinceridad. Sin una comunicación sólida, es fácil que surjan problemas con tantos pasos repartidos entre diferentes personas. Por eso creo que una de mis tareas es mantener un estrecho contacto con todo el equipo. Siento que esto es cierto tanto en el trabajo como en la vida misma.

Y en el mundo de los tejidos Nishijin-ori también nos enfrentamos a una grave escasez de sucesores que perpetúen nuestra artesanía, ya que las oportunidades de usar kimono disminuyen y los artesanos actuales envejecen. Pero me esfuerzo al máximo para ayudar a conectar a la próxima generación con estas técnicas propias de la capital milenaria de Kioto y con el espíritu de nuestros predecesores en este oficio.

Monumento a Nishijin

Monumento a Sonko Okamoto

Reserva de experiencias

Experiencia individual de tejido Nishiki-ori con un maestro artesano (Wabunka)