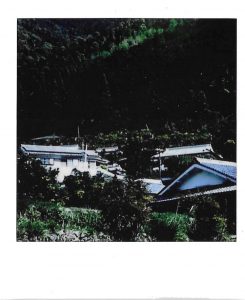

Mizuo is a village on the north side of the Hozukyo Gorge, upstream from Sagano and Arashiyama. The village’s history dates back to the Heian Period (794-1185) and it is where Emperor Seiwa (850-880) had chosen as his final resting place.Mizuo has also been an important place of transportation crossroads. One of the pilgrimage paths leading up to Atago Shrine, famous for its deity that is said to prevent fires, on the summit of Mt. Atago forks from here. It is also where the Akechi Pass is, named after the warlord Akechi Mitsuhide who took the route when he led the famous coup (the Honno-ji Incident) in 1582.

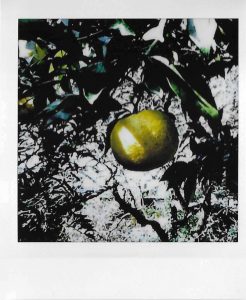

This historical village is also known as “the village of yuzu.” The citrus fruit, yuzu, from Mizuo are especially large and aromatic. The yuzu is not only used at high-end Japanese restaurants but also has attracted guests from across the country to come and enjoy the fragrant yuzu baths and yuzu-flavored chicken soup called tori nabe.

Mr. Kazuhiko Murakami, the representative of Kyoto Mizuo Agricultural Products who has been living in the village for sixty-nine years, will take us on a journey to discover the charms of Mizuo.

Kazuhiko Murakami’s story

If you drive through the thick cypress woods for about fifteen minutes from JR Hozukyo Station, you will see a sign saying, “The Village of Yuzu.” During the harvest season from autumn to winter, yuzu trees baring abundant fruit can be spotted throughout the village. Mizuo is said to be where the cultivation of yuzu began in Japan. Yuzu trees are originally from China, and it is not clear when or how they were brought to Mizuo. Some say it was at the order of Emperor Hanazono (1297-1348), and others say it was because Emperor Seiwa (850-880) loved the fragrance.

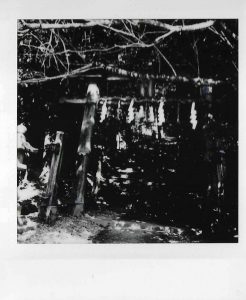

During the Edo Period (1603-1867) there were many rice paddies and nearly a thousand residents lived here at one point. “However, much is unknown because Mizuo suffered two big fires during the Edo Period and all the records were burnt,” says Mr. Murakami. According to what he heard from his parents, “Since the old times, forestry and yuzu cultivation have thrived here. The male villagers participated in the forestry and yuzu cultivation, and women sold branches of shikimi to the pilgrims visiting Mt. Atago as talismans to take home.” Mr. Murakami’s family is also one such farmer household that has been living in this mountainous village for generations.

Change came around to this village during the 1960’ and ‘70’s s as Mr. Murakami, who was born in 1952, was about to enter adulthood. Forestry began to decline, and the children who were anticipated to take after the business left to work for companies in the city. Many households lost their successors. Mr. Murakami was the only one in the village who continued to commute to work from the village. “I’m the only one among villagers my generation, now in their sixties or seventies, who has never left here. For forty years, since I started working for a company in 1971, I continued to leave home at half past six and take the train every day.

During the same period, the women’s association of Mizuo started a campaign to create a stable source of income for the village by providing yuzu baths and tori nabe to guests in local households. (Tori nabe: a type of chicken soup cooked in clear broth on a portable stove at the table) “At the same time forestry declined, Shikoku also begun growing yuzu which increased the number of areas producing yuzu in Japan, forcing the market to become competitive. Also, because yuzu trees have thorns, some amount of the fruit naturally have flawed skin. Providing yuzu baths was the result of attempting to find ways to use the yuzu that cannot be sold on the market because of such flaws.” Hence, they decided on providing yuzu baths and serving tori nabe, which was a local feast that the villagers only ate for New Year’s celebration and Obon (a series of Buddhist ceremonies for ancestral spirits which takes place in summer).

This idea of welcoming guests to local homes, allowing the guests to feel the unpretentious charm of Mizuo and enjoy getting to know the villagers, was a great success. Thanks to the good access from the urban areas of Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe, its popularity rapidly grew so much that about 15 households served yuzu baths and tori nabe in the busiest days.

For almost forty years, Mr. Murakami continued to commute to work on weekdays and helped his family business on the weekends, until he retired. Then, he decided that he wanted to engage more with yuzu and made an agricultural producers’ cooperative corporation in 2014, when he was 62. His active personality propelled him to take initiatives, expanding sales routes and pursuing his passion for yuzu. As a result, he gained business partners all over Japan and he incorporated the association in 2019. “I thought my business didn’t have a successor, but now my second son is willing to take over, so I hope to get everything on track while I’m still in good shape.”

Mr. Kazuhiko Murakami guided us through the past, present and future of the “village of yuzu.”

The pilgrimage road to Mt. Atago

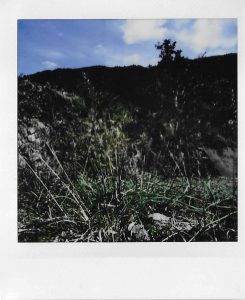

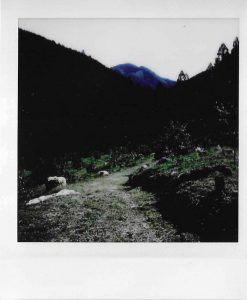

On the way from Mr. Murakami’s house to the yuzu orchards, Mr. Murakami paused for a moment. He pointed towards the mountains and said, “That’s Mt. Atago,” and continued, “Isn’t it a great view? I love this view.”

Mt. Atago, situated in the northwestern area of Kyoto City, is where Atago Shrine which has long attracted strong worship from Kyoto residents as where the guardian deity of the kitchen is enshrined. This village is at the western foot of Mt. Atago where a pilgrimage trail runs through, so it has always had deep ties with Mt. Atago. In the old days, the pilgrims who made their monthly visits would buy a branch of shikimi with thirty leaves as a votive, and would toss a leaf into the kitchen stove each day to pray for protection from fire hazards. (Shikimi: a type of evergreen tree that grows wildly, traditionally used as sacred offerings) The women of Mizuo were those who sold the shikimi branches.

A crossroads where various paths intersect

Before automobile became widespread, the villagers used to take a path only about a meter-wide on foot or pulling carts to the station. “My mother also used to walk to the station to get on the steam locomotive to go sell the yuzu at the market,” Mr. Murakami says. There is a range of paths that cross roads here, such as the “Komekai-Michi Path,” literally the “rice-buying path,” which people used to come from Kiyotaki on the east side of Mt. Atago to buy rice. Now, some of these paths underwent maintenance work and have become paths that hikers and cyclist comfortably enjoy the area’s nature.

The past and present of yuzu cultivation

After he retired and launched his new business, Mr. Murakami has purchased abandoned farmland and mountain property to cultivate and expand his yuzu orchards. Mr. Murakami’s yuzu cultivation is well-devised. According to him, “The yuzu trees around here grow tall, so we used to use ladders with 13 steps to pick the fruit, but now, I trim the trees to keep them short and easy to harvest.” He also says the grass covering the orchard’s ground, called rattail fescue, becomes a natural fertilizer after the stalks collapse by the weight of its seeds. This might explain why the yuzu trees in his orchards all look healthy with lush green leaves and large, well-grown fruit.

Mr. Murakami says that, in recent years, the natural environment of the forests has been disrupted, resulting in agricultural damage by deer and wild boars. The situation is obvious in the way the undergrowth and tree bark in the abandoned orchards are completely ravaged. However, the orchards of Mr. Murakami maintain thick undergrowth, showing a visible proof of his careful tending. Still, there are natural disasters such as typhoons and heavy snow that are inescapable. At one point, a series of consecutive damage to the orchard dropped the produce to nearly half. After years of arduous effort, finally, the harvest has recovered to near the level of its best.

Now that the orchards and his company are fine, it may seem as if all is going well, but he says he still has one problem unsolved. That is, about the future of Mizuo. “In this village, we in our sixties are the youngest of the generations. The households that continue the tori nabe and yuzu bath have halved over the years,” he says. Mizuo, like many other villages in the mountainous areas of Japan, inevitably faces a decreasing and graying population. Among the picturesque Japanese houses and yuzu orchards with trees bearing bountiful fruit, he says, there are abandoned houses and orchards. Also, whether community traditions, such as participation in shrine activities and holding annual ceremonies or events, could be continued or not is uncertain due to the lack of people. Thus, it is Mr. Murakami’s earnest wish to get the yuzu production on track and eventually make it possible to create employment which would allow yuzu cultivation to continue here.

The future of “the village of yuzu”

Within the seventy years since Mr. Murakami was born, the rice paddies and plum orchards by the river became cedar woods, and the 125-years old elementary school closed, drastically changing the way the village was. Not only the decreasing population, but also agricultural damage by wild animals, natural disasters and climate change remain persisting sources of difficulties. Nevertheless, there are new initiatives taking place, too. Mizuo is taking part in Kyoto Prefecture’s “Kyo Lemon Project,” aiming to grow lemons in Kyoto, which had been said that the climate is too cool to grow lemons until now.

Despite all the transition that has taken place in the village, there are some things that are still the same. Neither the clear flow of the stream that Mr. Murakami used to catch amago trout and eels as a child nor the dazzling yellow and green in the yuzu orchards before harvest have changed.

How about a visit to this village to explore both the changing and unchangeable?

Mizuo through the eyes of Kazuhiko Murakami