Bamboo has had a not-so-obvious yet essential role in Japanese culture as a ubiquitous element of its traditional lifestyle. As durable, easy to handle, and not-too-showy material; bamboo has been used in Japan for a wide range of products including garden fences, building material, tableware, and utensils for flower arrangement and tea ceremony. Hiroaki Nakagawa is the eleventh-generation successor of TAKEMATA, a shop that has focused on using traditional bamboo-working techniques to produce crafts that are adapted to the continual shifts in lifestyles occurring over centuries. We interviewed Mr. Nakagawa and asked him about today’s bamboo-working scene.

Bamboo Artisan Hiroaki Nakagawa

Hiroaki Nakagawa was born in 1971 in Kyoto city. After working at a housing construction company, he joined his family’s business at the age of thirty and began to learn the traditional techniques passed down from generations of artisans of TAKEMATA Nakagawa Takezaiten, which was established in 1688. He has since devoted himself to diverse areas of bamboo-working, from construction and garden-design to the production of daily-use implements and tea ceremony utensils.

Interview

—– Right near TAKEMATA is a street called “Takeyamachi”. The street name seems to suggest that there were once many other businesses handling bamboo (“takeya”) in the same area. Is that correct?

Apparently, there used to be quite a few (bamboo) workshops even just within this area, though they are mostly gone today. Bamboo was a very familiar material in the daily lives of Japanese people. So bamboo workshops must have stood side-by-side around here, each specializing in a different area like construction, gardening, or production of daily-use implements or tea ceremony utensils.

When first established, TAKEMATA was a wholesaler specialized in bamboo—a “bamboo merchant” that sold bamboo material to artisans who processed it and made crafts. It was only after entering the modern age that we started to process and assemble bamboo ourselves, taking part in the process of manufacturing things such as bamboo fences, construction material, and daily-use implements.

—– What areas of bamboo-working is TAKEMATA strongest in today?

Clients often give us work making “marumono” (literally “circular things”). These are made by processing bamboo that is in a form close to a cylinder. Such products that you often see in Kyoto would include the construction material used in sukiya-style architecture, komayose barriers for machiya-style houses, and bamboo fences for temples. The styles of bamboo fences are especially numerous as you can see by how they are named after the specific temples that use them, such as “Kennin-ji Temple fence” or “Koetsu-ji Temple fence.”

Also, since TAKEMATA started out as a bamboo wholesaler, we are used to handling a wide range of bamboo types. So we do a lot of “henso” as well, which is the weaving of products such as baskets from thinly-split strips of bamboo. Our strength is in our ability to fulfil diverse demands related to bamboo.

—– It is said that over five hundred varieties of bamboo grow in Japan. As a whole, there must be quite a variety of different characteristics.

In general, crafts are made using one or more of the three varieties: Madake bamboo, Mosochiku bamboo, and Hachiku bamboo. Adding to this some rare varieties, I think TAKEMATA usually has about twenty varieties of bamboo in stock.

At TAKEMATA, we mainly use bamboo that has been grown in Kyoto. A single variety could end up with completely different characteristics, depending on the climate and other environmental conditions of the place where it is grown. So we always stick to the same sources. The temperature changes drastically in Kyoto between summer and winter, giving us robust and dense bamboo. In addition, bamboo grows slowly in places with long cold seasons, compared to warmer regions, giving us culms with shorter intervals between joints. Such bamboo is highly valued, especially when it’s used for interior, because of its refined appearance that conforms to the aesthetic standards of sukiya-style architecture (often seen in tea ceremony rooms).

—– I understand that Kyo-meichiku (literally “brand bamboo of Kyoto”) has become a synonym for bamboo-works from Kyoto. What sort of bamboo does Kyo-meichiku refer to?

The term meichiku (literally “brand bamboo”) refers to bamboo with artificially added looks and feels resulting from processing during growing or after harvest. In Kyoto, we often use bamboo for accents in architectural design. So, many meichiku have emerged here. Well-known among the meichiku is the “shiratake” (literally “white bamboo”) that is made by removing the bamboo’s oil and then exposing the timber to sunlight. This process results in a look that is different from the natural, green timber. The shiratake bamboo later gains a distinctive, light-amber color as it ages.

Another meichiku called zumenkakuchiku is produced by placing a square, wooden frame around the bamboo shoot when it has just come out of the soil. The resulting timber has a shape close to a square, giving it a very different character from that of the usual, cylindrical timber. Traditional bamboo-working begins at the stage of cultivation.

—– I see. So the bamboo-working of Kyoto has thrived on the meichiku supplied from the bamboo forests over in the Rakusai area (the southwest area of Kyoto).

For bamboo-works, the quality of the material is essential. As craftspeople, we wouldn’t be able to use our skills to their fullest, if not for the people who manage the bamboo forests and grow good-quality bamboo. Bamboo being resilient plants that grow wildly in many places, may seem like unlimited material. However, the straight and undamaged bamboo we use for crafts is all hand-grown. In recent years, however, there has been a decline in the number of expert bamboo growers, and abandonment of bamboo forests is becoming a serious issue.

—– I understand that you started working with bamboo at the age of thirty. Were you taught how to handle bamboo since childhood? After all, you were born as the eleventh-generation successor of TAKEMATA, which has continued for over three hundred years.

No, not at all. Aside from helping my family with their work sometimes, I grew up touching hardly any bamboo. After graduating from college, I lived outside of Kyoto, working at a housing construction company. So it was only after I joined the family business that I began learning the skills in earnest. I must admit, it was a late start for an artisan.

I was in my late twenties when I started to consider joining the family business, thinking that “someone must pass on the heirloom skills,” although it was a big decision to quit the company I had been working at for nearly ten years.

—– So when you were in your teens and twenties, you had no intention to enter the family business?

My family has never told me they wished me to succeed the business. To be honest, succeeding the family business was not in mind at all until I was in my late twenties. However, my father (the tenth generation) used to seize every opportunity to introduce me to other people in the same trade, clients, and suppliers. And people would express their recognition of me as “the successor.” So I might have started to gain a sense of responsibility without knowing so. To think of it now, my father’s actions might have been subtle -very Kyoto-like – manoeuvres to make me succeed the family business (laughter).

—– I have heard the phrase: “three years of splitting bamboo; eight years of weaving.” There are certainly many things that one must learn in the bamboo-working trade, from basic preparation to processing and constructing.

The years of experience make a big difference in the world of handwork. There is no such thing as starting to learn a trade too early. In that sense, I think I was barely in time at the age of thirty to start acquiring the skills.

At first, there was so much pressure: I had to catch up with other artisans of my generation, who had started learning the trade more than ten years earlier than me, and as the successor I had to learn how to oversee the whole workshop. I feel like I just barely made it through the past fifteen years, and it wouldn’t have been possible without the guidance I received from my father, my uncle, and senior artisans.

—– I understand that you also actively participate in non-traditional bamboo-working projects.

Architects and designers often approach me with their ideas, asking me if I can make certain things out of bamboo. These things have included the interior of structures, tableware, light fixtures, and furniture. As a (bamboo) artisan, I don’t like to say “I can’t do it” if it’s related to bamboo.

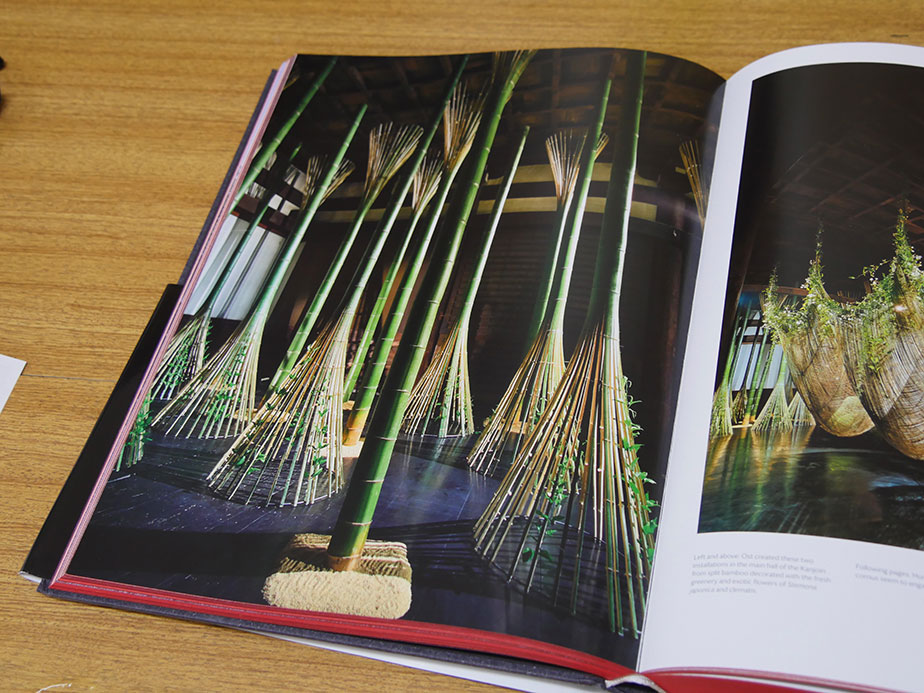

—– And in the works by Belgian floral artist Daniël Ost*, you have explored methods that are quite foreign to traditional bamboo-working.

I have continually participated in the production of his works since 2007. Based on sketches he drew, I select material and make many trial pieces for each work. The embodiment of an artist’s ideas is hard work, different from making handicrafts that follow specific, predetermined forms. But working with the artist always presents us with ways to use bamboo that we otherwise wouldn’t have thought of. So I enjoy the production processes. There is no one I know who examines and explores the possibilities of the bamboo plant more than Daniël Ost does, even though bamboo doesn’t grow wildly in Belgium. I and TAKEMATA as a whole treasure the opportunities to work with people like him.

Also, such applications of traditional skills to non-traditional bamboo-working create opportunities for me to test my own skills and imagination. Bamboo has been used in diverse ways throughout history. So we tend to assume that all possible processing and assembly techniques have been practiced by people in the past. But every time I work to fulfil contemporary tastes or embody artistic expressions, I am reminded that bamboo holds a huge store of unknown possibilities to explore and discover.

*Daniël Ost is a floral artist who was born in Belgium in 1955. He has carried out projects decorating many famous historical structures around the world with his works for clients including royal family members of Belgium and is known as the “floral architect.” He has held exhibitions at places such as Kyoto’s Toji Temple and Shimane’s Izumo Taisha Shrine in Japan. He was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun in 2015.

Nakagawa Takezaiten

610 Daruma-cho, Gokomachidori-Nijo-agaru, Nakagyo-ku, Kyoto