1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic that upended the world in 2020 had a massive impact on the tourism industry, and Kyoto was no exception. The scenery of Kyoto, which seemed to be overflowing with tourists in recent years, was suddenly enveloped in an atmosphere of tranquility, with some making nostalgic comments that “this is how Kyoto should be”. Conversely, the businesses that got into the tourism industry to take advantage of the inbound tourism boom showed no signs of keeping their momentum, and some lodging facilities that had been longtime favorites of travelers were forced out of business, making the past three years a time of extreme ups and downs. Nevertheless, everyone knows that Kyoto, which had been Japan’s capital for a thousand years, has experienced and overcome such difficulties again and again.

In this report, which is based on data we have collected and analyzed on a daily basis in our role as a DMO, we will go over the market trends of tourism in Kyoto both before and after the COVID pandemic, explain the measures we have taken in light of these trends, and focus on future prospects for the city.

2. Tourism in Kyoto in the Pre-Covid Era

2-1: A City Visited by 50 Million People from Around the World Each Year

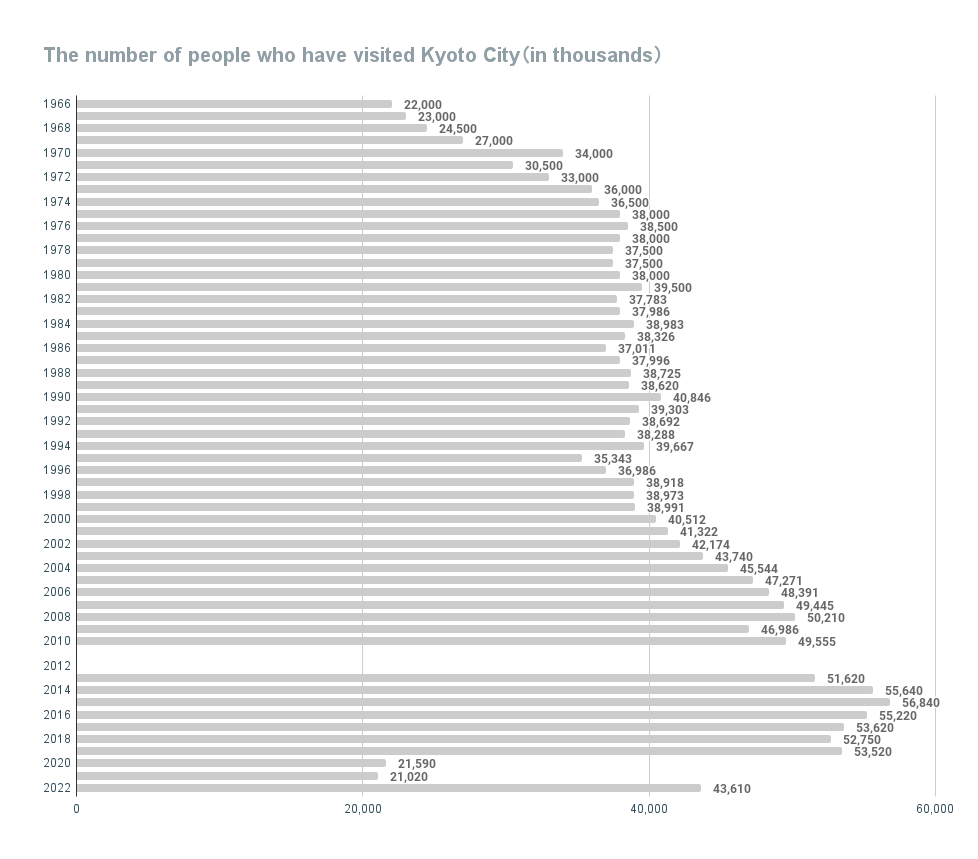

First, let’s take a look at the number of people who have visited Kyoto City [Fig. 1]. The first year that Kyoto recorded 30 million annual visitors was in 1970, the year that the Osaka Expo was held. The population of Kyoto City at that time was about 1.4 million, roughly the same as the population today, which means that many more people were already visiting Kyoto every year. Over the next 30 years, the number of visitors to Kyoto increased, reaching 40 million for the first time in the 2000s. The city then developed a plan to attract 50 million visitors, a move that was connected to the national government’s promotion of inbound tourism (known as the “Visit Japan Campaign”).

In the early 2010s, tourism took a hit due to the H1N1 influenza pandemic, the global recession triggered by the collapse of Lehman Brothers, and the Great East Japan Earthquake, but the number of tourists, mainly those coming from nearby Asian countries, surged as visa requirements for visiting Japan were eased and the rise of low-cost carriers (LCCs) coincided with the recovery from these disasters, peaking in 2015 at 56.84 million. Having reached its goal of 50 million annual visitors, Kyoto City changed its policy of pursuing quantity, shifting its focus to the quality of tourism, aiming to become a “tourist city that can be admired”. The number of foreign tourists continued to increase, but at the same time, the number of domestic tourists declined, bringing the total number of visitors down to the low 50-million range, where it remained for several years.

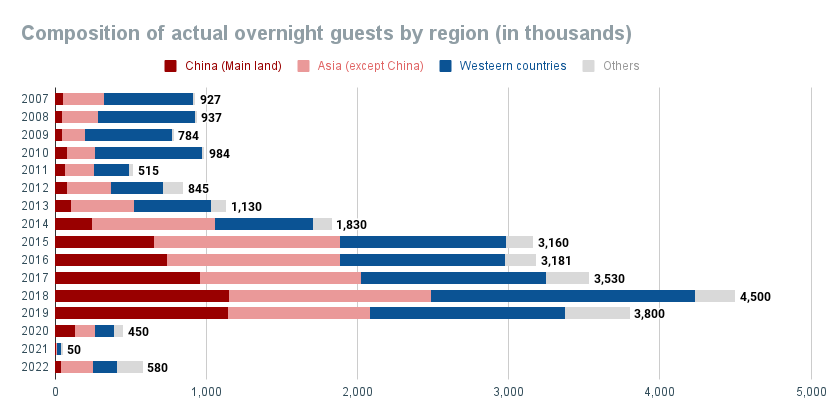

People may expect that visitors from abroad make up a majority of the visitors to Kyoto, as it often feels like foreign tourists outnumber Japanese tourists at many sightseeing spots. However, in 2019, the year before COVID hit, foreign tourists made up only 17% of the total number of visitors to Kyoto [Fig. 2]. This is less than the approximately 30% share of foreign visitors to Okinawa Prefecture (FY 2018 statistics), which indicates that Kyoto remains a popular destination for Japanese tourists. However, the majority of Japanese visitors are people living in the Kansai region visiting Kyoto on day trips, so when the data is restricted to include only visitors who stay overnight in Kyoto, the proportion of non-Japanese visitors increases significantly to around half of all visitors.

[Fig. 2]

Next, let’s take a look at a breakdown of the demographics of foreign tourists. Kyoto has always had a relatively large number of Western tourists, and up until 10 years ago, visitors from Western countries accounted for the majority of the total amount. From that point onward, the market in neighboring Asian countries has expanded rapidly, and the number of tourists from mainland China has grown to make up 40% of the total number. Even still, compared to the demographics of visitors to Japan by country/region on a national level, Kyoto has a comparatively large proportion of Western visitors, indicating that the city is a popular destination for tourists from a variety of regions. We’ll discuss the importance of this particular feature later on, when we address the impacts of the COVID pandemic.

2-2: Increased Tourism Consumption Driven by the Expansion of Higher-Priced Accommodations

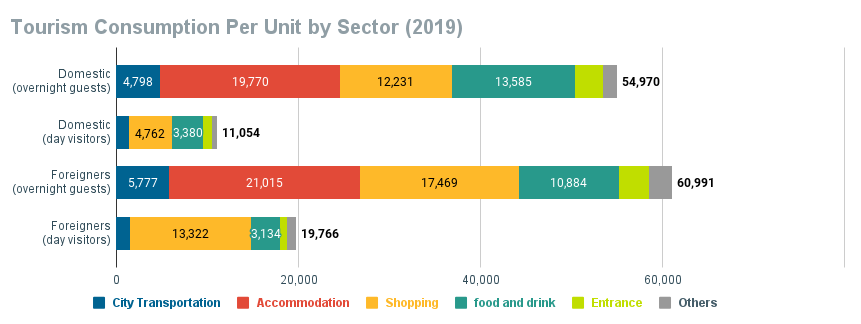

Tourists visiting Kyoto spent roughly 1.2 trillion yen in 2019, the year before the COVID pandemic [Fig. 3]. The added value generated from this spending comes to approximately 800 billion yen, equivalent to approximately 12% of the city’s total GDP.

[Fig. 3]

In 2019, the average spending per person was approximately 55,000 yen for Japanese overnight visitors and 11,000 yen for Japanese daytime visitors, compared to approximately 61,000 yen for foreign overnight visitors and 20,000 yen for foreign daytime visitors. There is little difference in spending between Japanese and non-Japanese overnight visitors, but up until a few years ago, that gap in spending was more than 10,000 yen. The main reason for the narrowing of this gap is higher lodging costs spurred by the increase in higher-priced accommodation facilities in the city. In 2014, the average lodging cost for Japanese visitors was around 11,000 yen, but it has nearly doubled since then. Over the past decade, the number of accommodation facilities in Kyoto with Michelin Guide five-star ratings has reached four, second only to Tokyo’s ten. Following the subsiding of the COVID pandemic, plans have been made for the opening of a number of world-class luxury brand hotels in Kyoto, so we can assume that lodging costs will rise even further, and other expenses associated with this increase can be expected to go up as well.

2-3: Tourism Issues that Arise Due to Lack of Supply

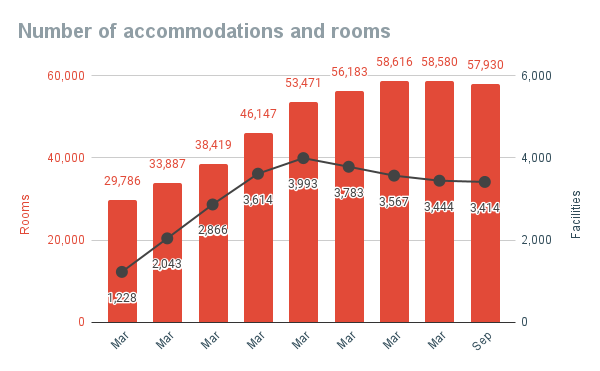

Before the rapid increase in foreign tourists visiting Kyoto, the number of guestrooms in the city was approximately 30,000 [Fig. 4]. Annual occupancy rates at major accommodation facilities reached nearly 90%, with popular establishments in a constant state of being nearly fully booked. In particular, domestic tourists tend to plan their trips later than tourists from abroad do, so by the time they decide to visit Kyoto, it’s impossible to get reservations at the hotels they want. This lack of available accommodations is believed to have been the reason why the number of domestic visitors to Kyoto started to decrease since tourist numbers reached their peak in 2015.

[Fig. 4]

Recognizing the need to increase the number of guestrooms available in the city to 40,000 in order to accommodate still-increasing tourist numbers, Kyoto City established the “System for Bringing High-Quality Accommodation Facilities to Kyoto City” in 2017 as a way to further improve its brand value. This system makes it possible to operate high-quality accommodation facilities even in areas where such facilities are typically restricted, and there are currently five projects in the works that are utilizing this system (the application period for new projects ended in March 2022).

However, even before this system was established, many businesses that saw the deficit in available guestrooms as a business opportunity began operating their own simple lodging facilities and low-priced accommodations in areas where such facilities were not restricted, and the number of guestrooms in the city quickly shot up to nearly 60,000. On top of that, the number of illegally run private accommodations also skyrocketed, with the city’s reporting office receiving as many as 1,000 reports of illegal operations per year.

Lack of availability became a pressing issue in terms of transit as well. Kyoto City Bus, whose route network was originally developed as a means of transportation for the daily lives of the city’s residents, has become the transportation method of choice for tourists as well, and the Kyoto City Transportation Bureau, which has been suffering from financial difficulties, has seen its situation steadily improving. However, one side effect is that user convenience has suffered and has become a considerable problem. On certain routes, the commuting demands of the general public overlap with the travel of tourists carrying large luggage, resulting in extreme crowding inside buses. This then causes people waiting at bus stops to miss several buses as the ones that arrive are already full and no more passengers are able to get on. To deal with this problem, a series of measures have been introduced, such as increasing baggage space in newer buses, running routes with stops only at major sightseeing spots, and placing attendants at stops with large numbers of deboarding passengers so that passengers can settle their fares after they get off the bus.

While improvements such as these have been made to address availability shortcomings in terms of both lodging and transportation, unfortunately, we can’t say with certainty that problems related to congestion and bad manners have been fundamentally resolved. The reason for this is that in Kyoto, where the aim of the branding was to gain admiration from all over the world, the structure has become such that as supply expands, new demand is created. Therefore, a different approach is needed to solve the problems caused by increased tourism in Kyoto. One of these is something we discussed earlier: increasing the per-person spending amount, mainly through the development of higher-priced accommodation facilities. In a broad sense, the introduction of an accommodation tax and the Kyoto City Certified Interpreter Guide System (a training system to produce top-level interpreter guides) are also part of the measures to increase spending.

The next factor is diversifying demand (which is equivalent to developing repeat visitors). For example, for more than 50 years, the Kyoto City Tourism Association has been holding special public exhibitions of cultural properties during the off-peak seasons of summer and winter, with the aim of attracting repeat visitors who are likely to be more responsive to attractions other than spring cherry blossoms and autumn foliage. Since around 2018, the city has also strengthened its efforts by introducing “Totteoki no Kyoto”, which highlights hidden sightseeing spots in six areas of the city, as well as early-morning and nighttime events. As a result of these efforts over the years, among domestic tourists visiting Kyoto, those who have been to Kyoto 10 or more times is as high as 60%.

These repeat visitors are familiar with the best places in Kyoto to visit and know how to avoid the crowds, so an increase in their numbers will have little impact on the daily lives of Kyoto residents. Around the same time in 2018, they also began forecasting congestion levels at major tourist destinations. Kyoto is a city where there is a lot of overlap between the flow lines of residents and tourists, and public spaces are often transformed into tourist attractions, which can make it difficult to establish entry restrictions. Therefore, by utilizing big data and publishing the congestion forecasts by the time of day several months in advance, we have been making efforts to encourage people to avoid congestion at their own discretion.

According to user surveys, approximately half of respondents indicated that they changed the date, time, or location of their visit after seeing the congestion forecasts. The forecasts are also used as one of the criteria for determining when to increase the number of extra buses on Kyoto City Bus routes.

The final factor, and the most difficult to measure, is the visualization of economic effects. As mentioned earlier, the data shows that the economic impact of tourism-based spending in Kyoto is equivalent to 12% of its GDP, but whether or not the residents of the city are seeing any actual benefit from this is another matter altogether. In the annual survey of Kyoto residents’ lifestyle experiences, when asked whether they think that “Kyoto is a comfortable tourist city to live in”, the majority of respondents answered positively, but the number of negative responses has been increasing year by year. Just before the outbreak of COVID, the negative responses had very nearly overtaken the positive ones. Revenue generated from the accommodation tax was being used to fund projects to address this issue, and measures were underway, but then COVID hit and everything ground to a halt.

3. Tourism in Kyoto During the COVID Pandemic

3-1: Who Was Able to Withstand the Sudden Market Changes?

In the spring of 2020, when the first state of emergency was declared, even when taking into account the fact that many of the city’s major hotels were forced to temporarily close, thus greatly reducing the number of guestrooms available, the occupancy rate plummeted to a record low of 6%. The average room rate also fell by as much as 40% or more, and for most of the period, except for some periods such as during the “Go To” campaigns, hotels were unable to recover their costs despite being open for business. The hardship faced by those in the industry, who continued to stay in business while relying on employment adjustment subsidies to keep their employees motivated and employed, is immeasurable. Those stores and facilities that were able to stay open were the lucky ones. Sadly, some businesses simply weren’t able to make it through.

Kyoto’s accommodation industry, which was already seeing incredibly fierce competition prior to the COVID pandemic, had seen an increase in the number of businesses closing, but the number shot up in FY2020 (April 2020 – March 2021) due to the COVID pandemic, with 632 businesses confirmed to have closed their doors for good in that one-year period. Reports of illegally run private accommodations, which had exceeded more than 1,000 per year, also dropped off, down to just a few dozen. On the other hand, the number of new business openings, while not as strong as in pre-Covid days, has remained at about half the number of business closures. The number of accommodation facilities in the city had been approaching 4,000 just before the pandemic struck, but has now settled down to around 3,500.

That said, the number has remained significantly higher than the 1,000 seen around 2014. Furthermore, the number of guestrooms hasn’t decreased that much from its peak of approximately 58,000. To summarize, guesthouses and other small-scale facilities were forced out of business by the COVID pandemic, while the large-scale facilities that were slated to be built since before the pandemic have been opening at a steady pace, though there were some delays in the opening dates.

Here, I would like to discuss a comparison of the facilities covered by the Tourism Association, broken down by location. The locations are divided into four categories: Kyoto Station Area, Downtown, Urban Area, and Other. A comparison of changes in the revenue per available room (calculated by multiplying the occupancy rate by the average room price, which corresponds to revenue per room; abbreviated “RevPAR”), which is considered the most important management indicator for accommodation facilities, shows that facilities in the “Other” category had recovered to their pre-Covid levels as early as the time of the “Go To” campaign of autumn 2020. Since then, the Other RevPAR has remained consistently higher than that of other areas, with some months in 2023 exceeding twice its pre-Covid levels. It should be noted that this “Other” category corresponds to the outskirts of the city, which are less likely to get caught up in the excessive competition seen in station and downtown areas, and the facilities located in these areas are characterized by their ability to attract visitors in a manner similar to famous tourist attractions. Even when taking into account the fact that the opening of a number of high-priced facilities in “Other” areas after COVID created an upward bias in the numbers, the data suggests that these branded facilities were less affected by the pandemic. In fact, wealthy travelers were able to travel in ways that avoided crowds and without worrying about being seen by others, even in the midst of the pandemic, by securing their own private spaces by block-booking entire facilities and vehicles, thus reducing the risk of infection from others. As such, higher-priced facilities were likely to be the recipients of such demand. Conversely, facilities in the vicinity of train stations competing with one another are still in a difficult situation, as their RevPAR figures are below the pre-Covid levels in 2023.

Next, let’s take a look at the impacts of the Covid pandemic on different markets according to data broken down by the region from which overnight visitors come. Naturally, the number of overnight visitors dropped sharply for all regions due to the pandemic, and the tourism industry was supported by overnight visitors from neighboring regions in Japan and national support for travel, a phenomenon that had never existed before COVID.

As restrictions on inbound travel started easing in October 2022, the first country to see a recovery in demand was South Korea. The transfer of government power to a new administration coupled with improved sentiment toward Japan, as well as its closeness, which makes it less susceptible to fuel surcharges, contributed to a rise in overnight demand to the extent that October 2022 figures surpassed those of the same month in 2019.

The next regions to show a recovery in demand were Hong Kong and Taiwan, and then the following spring, tourists from Western countries, who have a tendency to take time when planning and arranging travel to Japan, also returned to see the spring cherry blossoms. The following summer, individual travelers from mainland China began to increase as well, and I was surprised to see that China had become the top region as early as July 2023, even before the ban on group travel had been lifted. In the fall, Western tourists will again make up a larger proportion, and the Chinese market is finally expected to make a full-fledged recovery during February of next year during the Chinese New Year holidays. On the domestic side of things, accommodation provided by Japanese tourists, who provided a great deal of demand during the pandemic, is rather stunted in its recovery. Even if reservations by foreign visitors are made well in advance as they were in the pre-Covid era, the occupancy rate should still be around 70% due to there now being more accommodation facilities available, so there shouldn’t be a situation in which Japanese visitors want to make reservations but are unable to. That being said, if we were to pin down a specific reason for the lack of demand from Japanese tourists, it would have to be the increase in lodging costs. Average room rates at major hotels in the city surpassed pre-Covid rates by early 2023, due of course to an increase in inbound tourism as well as higher fuel costs and an increase in labor costs. A historically weak yen has also made traveling to Japan seem much cheaper for foreign visitors than it was before COVID. As more and more facilities take the bold step of setting their prices in response to this demand from inbound tourists, domestic travelers may feel that the current pricing is too steep, especially after having experienced discounted travel through means such as nationwide travel support.

Looking back on these varying trends in each market, we can recognize the importance of attracting customers in a balanced way, without relying too heavily on one specific market. Regions that were dependent on tourists coming from mainland China still have a long way to go before they fully recover from the COVID pandemic. In order to be able to cope with the possibility of risks such as natural disasters and political instability, we need to keep making efforts to attract customers from every possible direction.

3-2: Side Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic

There is no doubt that the COVID pandemic was catastrophic for the tourism industry, and it also forced the DMO to cancel many of the projects it had planned. This, however, also led to opportunities for us to try new things.

First, the Tourism Association was involved in running a subsidy program for measures such as ventilation and disinfection, which are necessary to dispel infectious disease-related concerns and ensure safe and comfortable tourism. In order to encourage its widespread use in the tourism industry, which has many small- and medium-sized businesses, the true value of the industry network that the DMO had cultivated up to this point was put to the test.

In order to handle the enormous amount of paperwork involved in the series of subsidy procedures, we were able to accept short-term, temporary assignments of staff from some of the city’s lodging facilities that had been forced to close, which also served as a way to maintain employment. While many of the assigned staff were likely bewildered by the unfamiliar work they had to handle, the fact that they were able to make contact with many businesses and reestablish industry networks was one positive outcome of the experience. The most significant result of these efforts is the “Declaration on Countermeasures to Prevent COVID-19 Infections (Guidelines)”, formulated in July 2020. While individual industries and businesses were attempting to devise their own measures in response to their specific situations, the DMO showed its leadership by announcing unified guidelines jointly with 23 major industry organizations in Kyoto [Photo 1]. Additionally, DMO Kyoto, which has made “industry support” one of the pillars of its management strategy, was able to further enhance this record by carrying out operations such as managing on-site vaccinations at workplaces and developing online training for telecommuting workers. When the government announced measures such as the “Go To” campaigns that started in the fall, as well as nationwide travel support measures the following year, they received industry feedback suggesting that only occupancy on weekends increased and that the gap between busy and quiet periods was no smaller. A campaign to promote overnight stays on Sunday nights was implemented in response. The trust we’ve built with the industry is what made it possible to design a system with similar effects as national campaigns yet with a much smaller budget, one based on occupancy rate data by day of the week provided by accommodation facilities.

There was also another significant advancement in the utilization of data: future forecasts. Restrictions on movement were imposed because of the COVID pandemic and we were in an ongoing state in which it was possible to get infected at any time. This led to travel plans being made on short notice, and it was difficult to predict demand. The Tourism Association thus began publishing occupancy rate predictions three months in advance by comparing reservation status and actual occupancy rates at accommodation facilities that had been providing us with data for a long time. We had originally received lots of inquiries from the media about future prospects, and these precise short-term forecasts created based on reservations have attracted a great deal of attention. These also contribute to the optimization of management practices such as planning purchasing, procurement, and employee work scheduling.

3-3: Advance Reservation Systems and CRM

I’d like to introduce one more way in which data can be used. For many years, the Tourism Association has run a special open house program for cultural properties as a way to provide activities for visitors during the off-peak seasons. Before COVID, a typical experience would consist of visiting the cultural property you wanted to see, paying a fee at the reception desk, and listening to an explanation of the facility from a guide inside the facility.

This way of doing things, however, sometimes caused congestion in the late afternoon hours or when large tours would visit, making it difficult to do during the COVID pandemic. To get around that, we introduced a reservation system so that we could continue the experience while also avoiding unwanted crowding. By setting a capacity for each time slot and having reservations made according to an itinerary, business was able to remain consistent. Since the overall number of visitors decreased, price increases couldn’t make up for the loss of revenue, but making visitors aware of the need to make reservations before sightseeing has promoted the use and development of other high-priced reservation-based products. Above all, the ability to utilize customer reservation and purchase data was a major step forward.

Specifically, in addition to analyzing total purchase amounts and frequency of purchases based on the purchase history of each e-mail address, we also periodically sent out the latest information to registered addresses as a way to ascertain their browsing habits. Those with high purchase amounts and opening rates are considered the “fan group”, and this group was given priority when sending information and special offers to encourage their attachment to Kyoto. This is the same level of customer management that all businesses of a certain size are engaged in, so in our role as a DMO, we would like to take this one step further. The essence of a DMO is making it possible for multiple companies to cooperate to achieve what a single private entity could not achieve on its own. In other words, the idea is to expand this mechanism to increase the number of fans so that it can be used by local businesses, as well as encourage businesses to develop special experiences available only to repeat visitors to Kyoto. Examples of this type of system may exist for local customers or for products that are purchased frequently, but I haven’t heard of any successful examples for destinations that aren’t frequently visited or for cities with a reasonable population and many people involved. However, it may be possible in the case of Kyoto, where 60% of domestic tourists have visited the city 10 times or more, which is a high proportion of repeat visitors. We hope you’ll keep an eye on what we try next.

4. Tourism in Kyoto in the Post-Covid Era

4-1: Turning the One-Two Punch of Labor Shortages and Higher Prices into Opportunity

The downgrading of COVID-19 to a Class 5 infectious disease in May 2023 ushered in a return to normalcy for most economic activities. The number of visitors to Kyoto is expected to recover steadily, but occupancy rates at major hotels in the city are hovering at around 70%, with no signs suggesting that they are likely to exceed 90% like they were before the pandemic. One obvious reason for this is that new hotels are opening and the capacity to receive visitors has increased, but another factor is thought to be that accommodation facilities are intentionally suppressing occupancy due to a serious shortage of labor. According to a one-time survey conducted by the Tourism Association around June, 70% of responding businesses have fewer employees now than they did in the pre-Covid era and feel that they are understaffed. This shortage is especially apparent in customer service positions.

It’s quite possible that a big reason for this is that the rapid recovery of inbound demand is coming at a time when a new supply of part-time workers, particularly foreign students, has stopped, and staff who are capable of providing service in foreign languages are also fewer. There is also a severe driver shortage.

According to the Kyoto Taxi Business Center, which is responsible for the registration of corporate taxis in the Kyoto area, many drivers quit or retired during the pandemic, causing the number of drivers to plummet from about 8,000 to roughly 6,000, which has resulted in a surplus of vehicles.

During school trip season, there’s a particular increase in demand for chartered taxis for group activities, and getting a taxi can be difficult even when using a taxi-dispatch smartphone app.

Rising expenses due to the increase in fuel costs are putting pressure on management as well. According to the 2022 edition of the Kyoto Tourism Business Survey, conducted annually by the Tourism Association, about 80% of respondents reported that costs had increased from the previous year, a figure twice that of the previous year’s survey. The ability to pass this on to prices will make a difference in terms of survival, but there are some cases where companies have turned a crisis into an opportunity through creativity and ingenuity. One example is of a business operator who had, in the past, reduced the price per person by providing services to customer groups of a certain size, but then made the decision to increase the price per person by limiting service to only one customer at a time, which also made it possible to provide more courteous customer service, leading to greater customer satisfaction and profitability. As previously mentioned when discussing the hotel data, the industry as a whole is under pressure to raise prices, but if businesses are able to boldly change their target price ranges and transition to a focus on providing hospitality to a limited number of customers with reduced staff, then they will be better prepared to weather the effects should another catastrophe along the lines of the COVID pandemic occur again.

The DMO itself is also focused on developing high-quality experiences. This year, with support from the Japan Tourism Agency’s Tourism Restart Project, we held test sales of premium spectator seating at the Gion Festival at a price of 400,000 yen per person [Photo 1]. Similar projects are being tested around the country and gaining a lot of attention, with strong opinions both in support and opposition of the idea. The important thing is not to simply raise the price, but to provide a satisfactory array of choices for tourists. Some people find enjoyment in watching from the free areas and finding their own unique angle on the festivities, while others find value in hearing from the people involved in the festival and use the opportunity to make donations toward preserving the culture of the festival. In fact, the most popular response from those who purchased premium seating was that participants in the Yamahoko float procession came close to their seats and spoke to them in English in a friendly manner.

Thanks to the proliferation of social media, the fun of finding your own spot and taking photos from your unique viewpoint has become more widely enjoyed, but the opportunity to get up-close with the people actually involved in the festival can’t be provided without sufficient effort and reason. It’s simply a matter of prioritizing the development of high-quality experiences to fully present options such as the latter to tourists. Our desire to satisfy both types of customers and leave no one out remains unchanged. That’s really what sustainable tourism is all about.

4-2: New Travel Experiences Starting in Kyoto

In order to respond to the full-fledged recovery of inbound demand, the congestion control measures that have been in place thus far will enter a new phase in the fall. First is the suspension of sales of the one-day bus passes that have been widely used by both residents and tourists alike. The decision to suspend sales was made after taking into consideration the fact that, despite its convenience, users were generally limited to using City Bus routes, which has greatly contributed to congestion. From now on, the passes will be sold as a combined “Subway & Bus 1-Day Pass”, which will allow us to strengthen proposals for travel that utilize both subways and buses.

Two bold measures are also in the works for the taxi industry: test runs of rideshare taxis, as well as combined freight and passenger transport.

It has been said that reasons such as laws and regulations in Japan make such programs difficult to implement, but the recent shortage of drivers has triggered a consensus within the industry that made it possible for us to implement these programs this fall. Rideshare taxis would allow different groups of passengers to share the same vehicle, though this would be limited to routes from Kyoto Station to Kinkakuji Temple. It would lower the fare per passenger, increase per-vehicle revenue, and also transport more passengers with fewer vehicles. Combined freight and passenger transport is a reservation-based system in which a taxi takes passengers to a sightseeing spot, the passengers get out, and the taxi then takes their large luggage directly to their accommodation. Innovation is always the result of facing challenges. Our hope is that the tourism-related issues Kyoto is facing will give rise to new travel experiences and become the new global standard.

4-3: Post-Renovation Reopenings in Full Swing

During the pandemic when tourist numbers were severely reduced, many facilities underwent extensive renovations. Kiyomizu Temple is a prime example of this. Nearly three years have passed since the renovation of the main hall was completed, so many of you may have already seen it, but I strongly recommend seeing how beautiful it is early in the morning.

It’s still a little-known fact that Kiyomizu Temple opens its gates at 6:00 in the morning. Shrines and temples aren’t the only facilities that have been getting work done on them. Hotels such as the Westin Miyako Kyoto and the Rihga Royal Hotel Kyoto have also undergone major renovations. Gion Corner, a popular spot for foreign visitors to take in cultural performances such as Geiko and Maiko dancing has just been renovated as well. On a site adjacent to that, the Imperial Hotel is slated to open a Kyoto location in the spring of 2026. Kyoto Racecourse, which underwent extensive renovations to mark its 100th anniversary, has recently become a new tourist attraction with a family-friendly focus, featuring playground equipment and horseback riding experiences. This past autumn, Kyoto department stores also had work done, with Takashimaya getting a full makeover and Daimaru redoing its restaurant floor. Furthermore, Kyoto City University of Arts has relocated its campus to the area on the east side of Kyoto Station, and the vicinity is expected to be revitalized as an art-themed area. It’s possible that had the COVID pandemic not happened, we wouldn’t be seeing such a massive number of renovation projects. We hope that visitors to Kyoto will continue to cherish their familiar haunts while also experiencing all the new things the city has to offer.

5. Aiming to Become a World-Class DMO

5-1: Initiatives as a Pioneering DMO

In March 2023, the Japan Tourism Agency, wanting to support the creation of “world-class DMOs” in Japan, solicited bids from DMOs throughout the country, and from among the applicants three organizations were selected.

One of those organizations was ours: the Kyoto City Tourism Association. With support from the Japan Tourism Agency and other experts, a two-year action plan will be formulated, which we will use as a roadmap to solve problems in a way that can serve as a model for the whole of Japan. We are very grateful for the support that the Japanese government has provided in helping industry make a strong recovery following the COVID pandemic and once again take on the challenge of competing with cities around the world.

One of the features of this support is that the subsidy system for research projects, which had only been available to wide-area DMOs, will now be available to regional DMOs at the basic municipality level. Particularly in Kyoto, one of the most challenging issues is fostering understanding of tourism among its residents, so our focus will be on analyzing the economic benefits of tourism and conveying the significance of tourism in an easy-to-understand manner.

Additionally, as symbolized by the premium spectator seating at the Gion Festival mentioned earlier, we’re developing comprehensive business plans that cover both upstream and downstream business, including things such as developing high-quality experiences that utilize cultural properties, supporting the development of products for inbound tourists and promoting interaction among industries, improving multilingual information signage, and improving the information distribution environment in cooperation with private-sector media.

We also want to take on the challenge of instituting internal reforms. Being an organization that is both governmental and private sector, in addition to full-time employees, there are also staff who have been temporarily assigned from government and private-sector positions, specialized staff with fixed-term contracts, and part-timers who work at the Tourist Information Center. In a DMO where such a wide variety of workers coexist, our goal is to develop a clear path to evaluate each person’s performance and encourage their growth. Boosting membership fee revenue by way of acquiring more new members and reforming the membership fee system is also a theme of particular importance. We hope you’ll keep an eye on future developments.

5-2: Conclusion

For better or worse, the COVID pandemic allowed us an opportunity to rethink our previous efforts. Many businesses were able to survive the ordeal thanks to the horizontal connections they had maintained with local communities, residents, and industry. Businesses that sought to develop high-quality experiences were able to recover more quickly from the effects of the pandemic. Such businesses are essential when it comes to preparing for the possibility of another such crisis in the future and to achieving sustainable tourism. Utilizing data also made it possible for us to look ahead and promote consensus-building within the industry. Positive challenges for the future continue, including bold congestion control measures and major facility renovations.

It is said that the Meiji Restoration of 1868 decimated the city of Kyoto to the extent that it was said to “eventually be home to only foxes and raccoon dogs”. However, instead of just lamenting this idea, the residents of Kyoto worked together to modernize the city, and it has since grown into a place that maintains its traditional culture to this day while also attracting visitors from around the world. A pandemic like the one we have just been through may have been a challenge for those of us living today, but overcoming it has made us realize over the past three years that the feelings of those Kyoto residents in the wake of the Meiji Restoration have been passed down to us today. By looking back on the thousand years of history that have been carried on in such a way, we can surely have a sense of hope that Kyoto will continue existing as it is for a thousand years more. It is precisely because we live in an age of uncertainty that we should fulfill our role as a world-leading DMO and support the tourism industry so that people all around the world can feel the hope that this city can bring.

Article Author