그 형태는 인간의 모습이지만, 인간이 아니다.

불교 조각품의 제작은 "기키(己き)"라는 의식 규칙에 따라 엄격하게 관리됩니다. 얼굴 표정, 손가락 모양, 자세에 이르기까지 모든 세부 사항이 불교 사상의 표현입니다. 붓시(Busshi)라고 불리는 불교 조각가들은 붓다의 가르침을 정확하고 장엄하게 표현하기 위해 자신의 기술을 연마합니다.

한 가지 예외인 불상이 입는 천상의 가사는 의식 규칙에 거의 언급되지 않습니다. 정해진 규칙 안에서 작업해야 하는 불교 조각가들에게 가사는 자신만의 창의성을 불어넣을 수 있는 몇 안 되는 영역 중 하나입니다. 발이나 천의 겹쳐진 주름을 향해 흐르는 가사의 질감을 묘사하는 데는 정해진 정답이 없습니다. 조각가는 왼손에는 끌을, 오른손에는 망치를 들고 시행착오를 거치며 나무를 조각합니다. 마치 진짜 옷처럼, 하지만 위엄을 잃지 않습니다. 장엄한 위엄과 현실 사이에서 작업하며, 조각가는 마음속에 그려지는 부처의 모습을 바탕으로 작품을 만들어냅니다.

미야모토 가큐

불교 조각가. 1981년 교토에서 태어났습니다. 고등학교 졸업 후 미술 단기대학과 전문학교에서 패션 디자인을 전공하고 일러스트레이터로 활동하다가 교토에서 불교 조각가로서의 수련을 시작했습니다. 2015년, 9년간의 수련을 마치고 자신의 공방인 미야모토 공예를 설립하여 불교 조각과 수리 작업을 하고 있습니다.

불교 조각가의 중요성

불교 조각가 미야모토 가큐는 자신의 스튜디오에서 만든 불교 조각상을 우리에게 보여주었습니다.

"이것은 불에 타서 완전히 검게 탄 나무 조각이었습니다."

“한 사찰의 교구민 집에 화재가 발생하여 주지 스님이 위문품으로 불상을 제작하도록 의뢰했습니다. 집은 모두 소실되었지만, 느티나무로 만든 중심 기둥은 그대로 남아 있었습니다. 끌로 표면을 깎아내니 그 안에 석가모니(부처님)의 모습이 이제야 보이기 시작했습니다.”

100년도 더 된 집에 쓰인 느티나무였으니, 아마도 200년도 넘었을 겁니다. 불길에 표면이 거의 완전히 탄화되었지만, 미야모토는 조심스럽게 끌질을 하면서 점점 싱싱하고 젊은 나무가 드러나기 시작했다고 말합니다.

미야모토는 약 9년간의 수행 기간을 마치고 2015년에 스승을 떠나 독립했습니다. 이는 그가 불교 조각가가 된 이후 처음으로 받은 불상 제작 의뢰였습니다.

미야모토 공예를 시작한 후, 첫해는 주로 위패(位貝, 위패)와 같은 조각 작업을 했습니다. 불교 조각가로서 당연히 불상을 만들고 싶었지만, 불상 제작에는 운명적인 요소가 있기에 그저 기다릴 수밖에 없었습니다. 불상을 태운 나무로 불상을 만드는 것은 흔치 않은 일이지만, 독립 후 받은 첫 불상 의뢰가 의뢰인에게 깊은 감정적 의미를 지닌 작품이어서 정말 기쁩니다. 수련 기간이 끝나고 처음 독립했을 때도 불상 제작의 의미에 대해 끊임없이 고민했습니다. 왜 불상을 조각하는지 늘 스스로에게 질문했는데, 이번 불상을 만들면서 그 답을 찾을 수 있을 것 같습니다.

미야모토의 손에 안겨 있는 불상. 끌을 조심스럽게 움직일 때마다 불상의 형태에 생명력이 불어넣어진다.

패션과 불상

미야모토는 미야모토 다카유키라는 이름으로 태어나 교토 남부 후시미 구에서 자랐습니다. 그는 어떤 길을 걸어 불교 조각가 미야모토 가큐가 되었을까요?

그는 항상 패션에 관심이 많았습니다. 중학교 졸업 에세이 모음집에서 젊은 시절 미야모토는 패션 디자이너가 되고 싶다고 썼습니다. 고향 고등학교를 졸업한 후, 그는 예술 단기 대학의 패션 디자인 프로그램에 입학했습니다. 예술과 패션 표현을 공부하면서 그는 형태의 아름다움을 추구하는 디자인에 매료되었습니다. 졸업 후, 그는 장학생으로 도쿄의 직업 디자인 학교에 입학했고, 패션 디자인의 세계에 더욱 깊이 빠져들었습니다.

실용성보다는 예술 작품으로서 옷의 아름다운 형태를 좋아했습니다. 당시 유럽 오트 쿠튀르에서 유행하던 장식적인 패션을 동경하며 저만의 접근 방식을 탐구했습니다. 패션 디자이너 존 갈리아노처럼 되고 싶었죠. 전문대에서 2년, 직업학교에서 3년 동안 패션을 공부했지만, 막바지에는 재봉틀을 사용하는 것보다 디자인 스케치를 그리는 것이 더 재미있었습니다. 결국 직업학교를 휴학하고 그림을 그리기 시작했습니다.

패션 디자인 분야에서 시작한 미야모토는 전시회에 작품을 선보이기 위해 열정적으로 작업하기 시작하면서 추상화 분야로 영역을 확장했습니다. 하지만 도쿄에서 아르바이트와 창작 활동의 압박 속에서 살면서 스물네 살이 된 미야모토는 어려움을 겪기 시작했습니다.

"지쳐서 제가 자란 교토로 거점을 옮기기로 했습니다. 디자인 사무실에서 아르바이트를 하면서 제 작품도 계속 만들었고, 어느새 자리를 잡고 있을 때 스승님을 만났습니다."

불교 조각가의 작업실을 방문한 것은 처음이었다. 형의 불교 조각가 친구의 일손이 더 필요해지자 형이 데려온 미야모토는 7척(약 2.1미터) 높이의 미완성 십일면관음상을 보았다. 형은 그를 스승에게 소개하여 완성을 위한 마지막 관문 중 하나인 채색 작업을 돕게 했다. 미야모토는 이전에는 불교 조각에 관심이 없었지만, 붓을 쓰는 아르바이트를 하게 되어 기뻤다. 그 후 6개월 정도 미야모토는 낮에는 그래픽 디자인 작업을 하고, 밤에는 불상 앞에서 붓을 휘두르는 이중생활을 했다.

끌과 대패. 이상적인 형태를 추구할수록 도구의 수는 늘어납니다. 관리와 유지 보수에도 많은 시간과 노력이 들어갑니다.

당시 두 직업의 엄청난 시간 차이가 저를 괴롭혔습니다. 한편으로는 단기간에 소모되는 그래픽 디자인이었고, 다른 한편으로는 수백 년 후에도 지속될 작품을 만드는 일이었으니까요. 불상 작업은 즐겁고 깊이 있는 작업이었습니다. 쉬지 않고 일하다 보니 몸은 지쳐 있었지만, 매일 밤이 오기를 손꼽아 기다렸습니다. 그 순간, 저는 제 감정을 멈출 수 없었습니다.

미야모토는 한때 패션과 그림에 관심이 많았지만 불교 조각에 눈을 뜨자마자 더 이상 만족할 수 없었다.

"이전에 있었던 일과 앞으로 있을 일. 생각할 것이 많았지만, 어느새 스승님께 절을 올리고 제자로 삼아 달라고 간청하고 있었습니다. 이미 불교 조각의 매력에 푹 빠져 있었죠."

잠시 생각한 후, 스승님은 승낙하셨습니다. 스물다섯 살에 새 도제가 되는 것은 장인으로서는 늦은 시작이었습니다.

스튜디오의 내부는 조각가의 작업실이라기엔 너무 깨끗하고 정리되어 있는 듯하다.

호화로운 훈련

불교 조각가에게 수련은 힘들고 오랜 시간입니다. 조각 외에도 불상을 만드는 데 필요한 채색, 옻칠, 금속박 등 여러 가지 기술을 배워야 합니다. 게다가 불교 조각가의 작업에서 중요한 부분을 차지하는 수리 및 복원 작업에는 새로운 불상을 만드는 데 필요한 기술이 요구됩니다. 대부분의 장인들은 긴 수련 기간을 기대하며 10대에 이 세상에 발을 들여놓습니다. 미야모토가 수련을 시작한 25세는 다른 장인들이 수련을 마치고 독립된 불교 조각가로서 독립하기 시작하는 시기입니다.

"처음 견습생이 되면 아무것도 할 수 없어요. 무력감이죠."

미야모토는 조각칼을 잡는 법도 몰랐고, 하물며 조각하는 법도 몰랐다. 그는 날마다 아무것도 할 수 없다는 사실에 좌절하며, 그저 스승의 작품을 지켜보기만 했다.

아무것도 할 수 없는데 스승님께 돈을 받는 게 너무 속상했어요. 그 시절을 떠올리면 가장 크게 기억나는 건 미안하고 스승님께 사과하고 싶었던 마음이에요. 아무것도 몰랐기에, 한 가지라도 더 하려고 밤에 필사적으로 연습했어요. 어떤 날은 조각상의 손 모양에 집중했고, 어떤 날은 무늬에만 집중하며 스승님이 낮에 하신 일을 떠올리곤 했죠.

미야모토는 스승의 첫 제자였습니다. 그의 스승은 아무것도 가르쳐 주지 않는 구식 수행을 통해 불교 조각가가 되었고, 제자는 스승을 지켜보며 그의 기술을 훔쳐야 했습니다. 그러나 스승은 미야모토에게 "모든 작업을 보여주고 질문에 답해 주겠다. 그러니 서둘러 기술을 연마하라."라고 말했습니다. 그는 약속대로 모든 작업을 자세히 설명해 주었습니다.

"제 나이를 고려하신 것 같아요. 언젠가 독립된 불상 조각가가 되려면 아직 젊을 때 기술을 익히는 게 최선이죠. 제 수련은 아주 호사스러웠어요. 스승님 맞은편에 앉으면 스승님께서 직접 조각하신 것을 건네주시곤 했죠. 스승님이 하시는 대로 조금씩 조각하면, 스승님께서 바로 앞에서 제가 한 일을 수정해 주시곤 했어요. 그렇게 수련할 만큼 운이 좋은 불상 조각가는 많지 않을 거예요. 스승님께서 해주신 덕분에 9년 만에 어느 정도 수준에 도달할 수 있었던 거죠."

미야모토는 스승의 첫 제자였기에 불교 조각가가 하는 모든 작업을 경험할 수 있는 행운을 누렸습니다. 또한 스승에게서 배운 기법을 후배들에게 전수하며 복습할 수 있었습니다. 그리고 2015년 4월, 미야모토는 9년간의 수련을 마치고 스승을 떠나 홀로 작업하게 되었습니다.

복원을 기다리는 불상 조각품들. 세척 후 분해된 상태로 건조 중입니다. 각 조각품은 과거의 유물입니다.

자기 없이

미야모토는 독립 후 불교 조각가로서 사용할 이름으로 "가큐(加久)"를 선택했습니다. "자아(自我)"와 "휴식(休食)"을 뜻하는 한자는 합쳐져 "자아 없음"을 의미하며, 때때로 스승과 다투곤 했던 미야모토에게 지나친 자기주장에 대한 경고이기도 했습니다.

저는 리큐(역사적인 다도 스승)의 예를 따라, 명성이나 재산을 추구하지 않고 사는 원칙에 따라 '명성도 재산도 없이'라는 선(禪)의 고사에서 이름을 따왔습니다. 불교 조각가는 자신의 작품에서 개인적인 감정을 억눌러야 하지만, 제 의견은 항상 표면으로 드러납니다. 그 말을 들을 때마다 그 교훈을 되새기고 싶어서 이 이름을 선택했습니다.

그는 마츠노오타이샤 신사 근처의 조용한 주거 지역을 자신의 스튜디오와 거주 공간으로 선택했습니다.

이곳은 강과 산으로 둘러싸여 있고, 일 년 내내 습도가 일정합니다. 나무를 관리하는 것은 불교 조각가의 중요한 업무입니다. 교토 곳곳을 돌아다니며 좋은 곳을 찾다가 결국 이곳으로 오게 되었습니다. 수련생 시절부터 같은 곳에서 살고 일하고 싶었습니다. 그래서 독립해서 처음 시작했을 때 가장 큰 목표는 불교 조각가로 일하기에 적합하고 가정생활에도 편안한 곳을 찾는 것이었습니다.

미야모토 공예에 처음 들어서면 공방의 정돈된 모습이 눈에 띕니다. 작업대 위에는 도구가 하나도 놓여 있지 않고, 바닥에는 나무 깎은 조각 하나 없습니다.

"도구나 재료가 빠져 있는 걸 보면 정말 속상해서 틈틈이 정리를 해요. 여기 오시는 분들이 '정말 여기서 일하시는 거예요?'라고 놀라시더라고요. 장인이라면 정리가 중요한데, 이렇게 꼼꼼하게 하는 건 제 성격 때문인 것 같아요."

자신의 로브 묘사

독립한 이후, 미야모토는 자신만의 불상 묘사에 대해 생각하기 시작했습니다. 그는 이를 통해 자신이 한때 공부했던 패션에서 비롯된 형태의 아름다움이 그의 마음속 불상과 겹치게 되었다고 말합니다.

부처상에 천이 드리워지는 방식, 주름, 그리고 몸을 따라 늘어지는 방식까지, 제 패션 디자인 경험을 이러한 표현에 활용할 수 있을 것 같습니다. 부처는 사람의 형상을 하고 있지만, 사람이 아닙니다. 역동적인 느낌을 주는 옷을 통해 부처의 장엄함을 더욱 강조하고 싶습니다.

불상은 "기키(己き)"라는 규칙에 따라 관리됩니다. 얼굴 표정, 손가락 모양, 자세에 이르기까지 모든 세부 사항이 불교 사상의 구현체입니다. 이러한 규칙은 과거의 기본적인 형태를 보호하고 계승하기 위해 존재합니다. 단 하나의 예외인 불상이 입는 옷은 의식 규칙에 거의 언급되지 않습니다. 결과적으로 불교 조각가들은 실제 옷처럼 자신만의 창의성을 불어넣을 여지가 있지만, 위엄을 해치지 않습니다. 미야모토는 장엄한 위엄과 현실 사이에서 작업하며, 마음속에 있는 부처의 모습을 바탕으로 작품을 만들어냅니다.

패션 디자인, 회화, 그래픽 디자인 등 전혀 관련 없는 분야에서 일해 왔다고 생각했는데, 틀렸어요. 불상 제작에는 어떤 경험이든 유용할 수 있고, 활용되어야 해요. 그래야 제 작품이 될 수 있다고 생각해요.

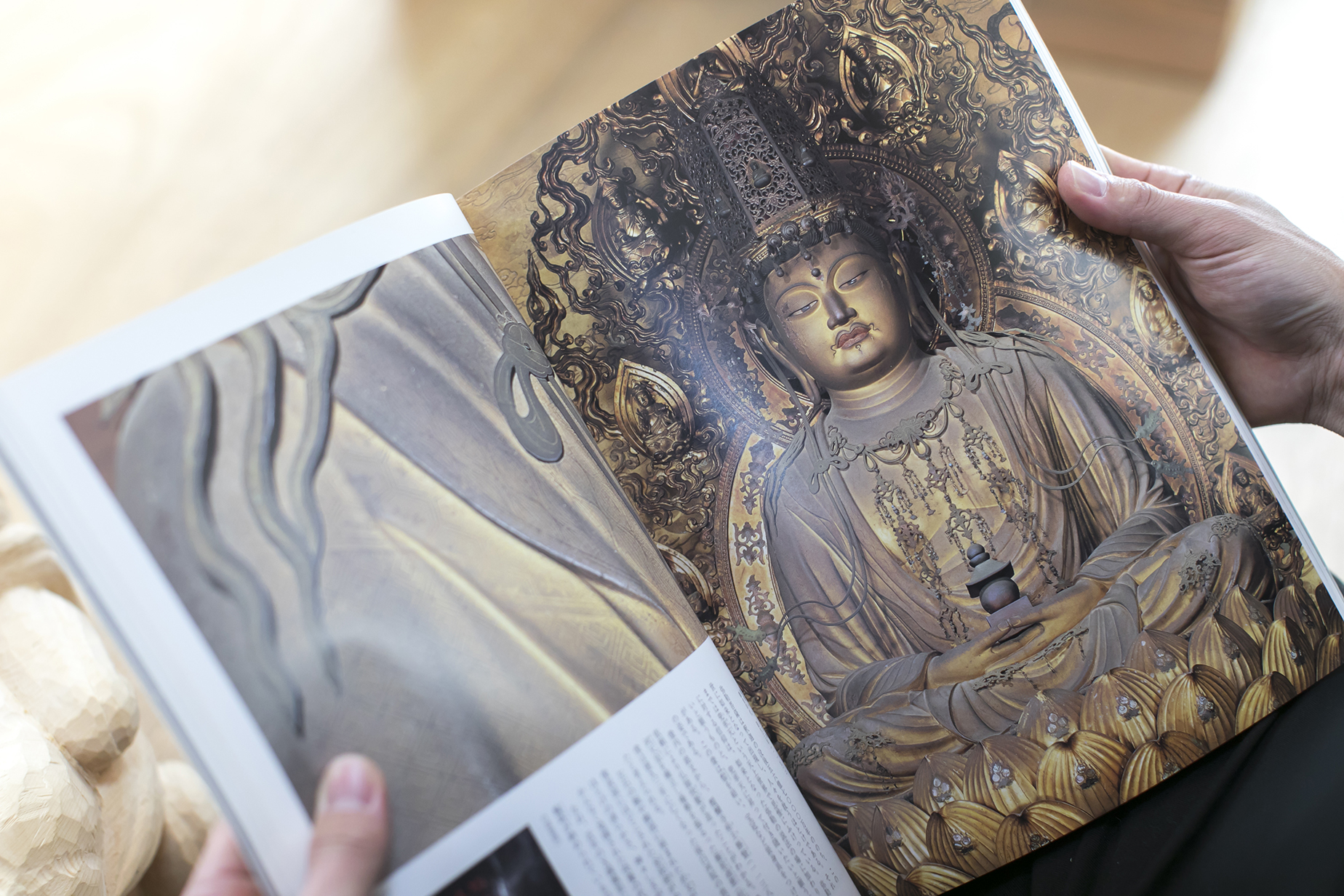

미로쿠보살좌상(다이고지 산보인 본존) 가이케이 작품.

현대 불교 조각가의 작품

“미로쿠보살좌상, 다이고지 산보인 본존상.”

미야모토는 이상적인 불상에 대한 질문을 받았을 때 거의 즉각적으로 대답했습니다.

"제가 견습생이었을 때부터 이 불상에 무엇보다 감탄했습니다. 쉬는 날에는 쌍안경을 들고 다이고지 절에 자주 갔죠. 가이케이(가마쿠라 시대 불교 조각가)의 통일성, 활기찬 에너지, 그리고 복장은 이 불상을 모든 면에서 제게 이상적인 불상으로 만들었습니다." 미야모토는 말을 하다가 낡고 너덜너덜한 그림책을 펼쳤다.

눈과 코의 대칭적인 위치, 그리고 곧은 코. 저는 카이케이 불상의 완벽한 대칭이 불상의 장엄한 위엄을 만들어내는 주요 요소라고 생각했고, 그 이상을 추구했습니다. 그런데 갑자기 모든 것이 뒤바뀌는 일이 일어났습니다.

그 행사는 그의 수행 기간 말미에 박물관에서 열린 특별 전시였습니다. 오랫동안 흠모해 온 미륵보살상이 전시된다는 소식을 듣고, 미야모토는 설렘과 기대감으로 가득 찬 마음으로 전시장을 찾았습니다. 하지만 그곳에서 그는 완벽하다고 생각했던 그 형태가 약간 왜곡된 것을 발견했습니다.

처음 가까이서 본 미륵보살상은 생각했던 것만큼 대칭적이지 않았습니다. 다른 사람들에게는 큰 차이가 아니었지만, 저에게는 엄청난 차이였습니다. 다이고지 절이나 화첩에서 멀리서 보면 완벽하게 균일해 보였습니다. 미륵보살상 앞에 서너 시간 서서 아래에서 올려다보기도 하고 한쪽 눈을 감기도 했지만, 아무리 해도 대칭이 아니었습니다. 그때까지 완벽한 대칭이 불상의 아름다움을 좌우한다고 믿으며 실력을 갈고닦았지만, 목표를 잃어버렸습니다. 온몸의 힘이 빠져나가는 것 같았습니다.

그 후 1년 동안 미야모토는 불상을 조각할 수 없게 되었다.

독립을 이루고 마침내 감정이 해소되기 시작하자 그는 불에 탄 나무로 불교 동상을 조각하라는 의뢰를 받았습니다.

"대칭적인 미륵보살에 대한 제 이상형이 제 머릿속에서 너무 커져버린 것 같아요. 하지만 대칭이든 아니든, 그 실물은 제 상상을 훨씬 뛰어넘었고 말로 표현할 수 없는 신성함을 지녔어요. 형체미와는 전혀 다른 차원의 압도적인 존재감이었어요. 그때부터 저는 어떻게 하면 그런 부처를 조각할 수 있을지 고민해 왔어요."

미야모토가 작업할 때면 언제나 다이고지 사찰의 미로쿠 보살좌상 사진을 그의 옆에 놓는다.

카이케이조차도 당대에는 아방가르드였을 겁니다. 규칙도 중요하지만, 그보다 더 중요한 건 규칙에 얽매이지 않고 조각할 수 있는 창의력을 갖는 것이겠죠. 그 사실을 깨닫고 나서 저는 제 손으로 불상을 만들어 보겠다는 결심이 더욱 굳어졌습니다.

2017년 4월, 불에 탄 나무를 깎아 만든 높이 1척(약 33cm)의 석가여래입상이 완성되었습니다. 주문 후 약 1년간의 제작 기간을 거쳐 불상의 개안식이 거행되었습니다. 미야모토는 불길을 이겨내고 부처가 된 느티나무가 앞으로 오랫동안 가족을 지켜주기를 바라는 마음으로 불상에 "코엔(불꽃)"이라는 이름을 붙였습니다.

미야모토 가큐로서 제가 만든 첫 불상은 정말 값진 경험이 되었습니다. 제가 만든 것이 숭배의 대상이 되는 직업의 중요성을 깨닫게 된 것 같습니다. 장인으로서 그런 불상을 만들 수 있다는 것이 정말 큰 축복이라고 느꼈습니다.

미야모토코게이

웹 사이트 및 서비스

페이스북: 페이스북.com/미야모토코게이/

인스타그램: 인스타그램.com/gakyu01/